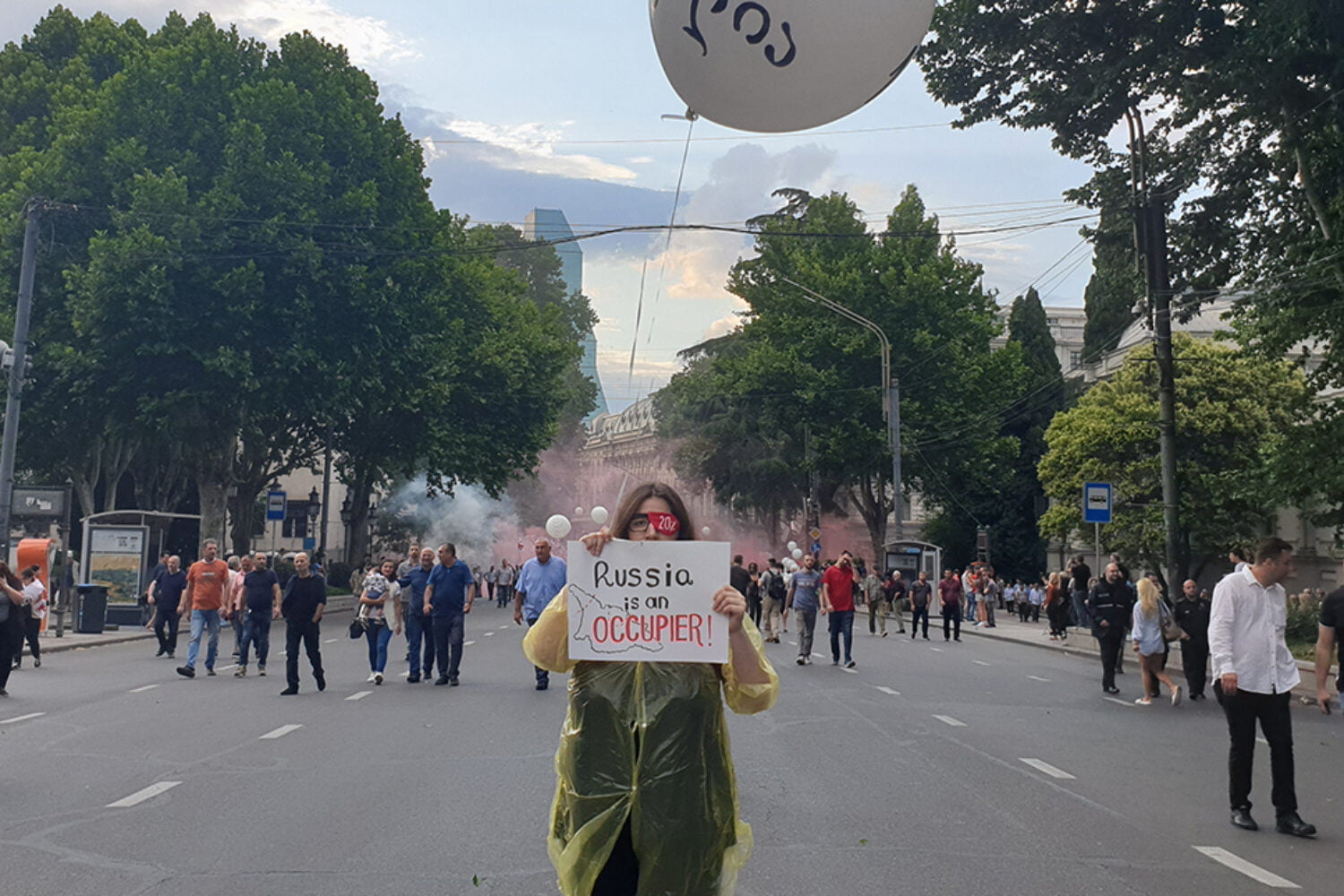

Protests and demonstrations are not uncommon in Georgia. However, the recent wave of protests that started on June 20 was still unexpected. The demonstration started against the Russian MP from the Communist Party, Sergei Gavrilov, who is also the President of the General Assembly of the Inter-parliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (IAO). Protesters were unhappy when he addressed the delegates of the IAO in Russian from the seat of the speaker of the Georgian parliament.[2] This means that the trigger for the Georgian public’s outrage was Russia, even if the root causes were related to economic and social grievances as well as issues related to Georgian-Russian relations, which Georgian citizens expect to be handled delicately. Demonstrators’ demands shifted to internal politics, however, following the violent dispersion of the June 20 rally by the police.[3] In response, the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) made some concessions. One, Parliament Speaker Irakli Kobakhidze resigned. Two, the GD committed to election reform: the majoritarian vote will be abolished for the 2020 elections and the polls will be fully proportional.[4] Although these issues require in-depth analysis, this article focuses on the spark that started the protests: Russia and its role in Georgian party competition.

Georgian political party manifestos and how they address Russia

Analyzing the role of Russia as an issue in Georgian party competition is a hard task as party competition is a complex phenomenon. Often, however, researchers focus on three important aspects of competition: the positions parties take on specific policy issues, the importance parties give to specific policy issues, and the issues parties try to claim under their ownership. On all these aspects of competition, conclusions can be drawn from the way political parties construct their manifestos before the elections.[5] For example, if Georgia’s integration into NATO is considered, the three parties that won seats in the parliament through proportional vote in 2016 —Georgian Dream (GD), United National Movement (UNM), and Alliance of Patriots of Georgia (APG)—established different positions in their manifestos. The GD and UNM[6] are both strong supporters for integration, while the APG’s position is more against than for integration in NATO. On the other hand, if the issue of relations with Turkey is considered, the APG has taken a strongly negative attitude toward Turkey, especially in comparison with the GD and UNM. In addition, neither the GD nor the UNM has stressed relations with Turkey in their manifestos as they choose to focus on the issues they view are more pressing for Georgian voters.

The treatment of Russia in the manifestos of the three parties, the GD, UNM, and APG, unfolds in an interesting manner. In terms of proportions, i.e. how frequently relations with Russia are discussed in relation to the length of the manifesto, the UNM takes the lead, attributing almost three percent of its entire manifesto to Russia exclusively (anything above one percent can be considered an important issue for a given party). Furthermore, the UNM only registers negative references to Russia, which makes it clear how the party views Georgian-Russian relations. This cannot be said, however, about the GD or APG.

Relations with Russia make up 1.6 percent of the GD’s manifesto. This means Russia is an important issue for the party. But the treatment is uneven: GD makes both favorable and unfavorable references to Russia. On average, two out of five mentions are positive about Russia in the party’s program. As a result, the GD sends unclear signals to voters regarding Russia because, while negative mentions are still more frequent, the positive mentions blur the line between the party’s positions.

Finally, the APG makes the fewest references to Russia out of the three parties. Georgia’s northern neighbor is mentioned in 1.1 percent of the APG’s manifesto. Just like the GD, however, the APG does not send a clear signal to voters about what kind of relations Georgia should pursue with Russia: more than 25 percent of references to Russia are positive, while the rest are unfavorable.

To sum up, the UNM tries to establish itself as an ardent critic of Russia and its influence on Georgia’s breakaway regions and, thus, tries to establish ownership of the issue of Russia in Georgian political discourse. However, this is not a simple task for the UNM and the recent protests have demonstrated how challenging it is for the political party.

Russia, protests and party competition

From 2003-2012, during the UNM’s incumbency, the then-ruling party created and hegemonized a highly negative political discourse on Russia. After losing the elections in 2012, however, the UNM suffered what can be called an identity crisis, which manifested in multiple disagreements and eventual splits within the party. Given that the UNM and GD do not register opposing views in their manifestos on any issue that is considered important, i.e. one percent space of the manifesto, the two parties compete in terms of which issues they stress as important and which issues they can monopolize as their own field of expertise. Russia serves as one such issue for the UNM. However, this is only one side of the coin.

The recent protests have demonstrated that the UNM and European Georgia (EG)[7] may enjoy the monopoly over Georgian-Russian discourse in party political discourse. But that is not the case when it comes to public discourse: the demonstrators did not allow the UNM to take over the protest wave and define it as a party rally. This has been a significant blow to UNM’s position in the Georgian political landscape. The demonstrators’ refusal to allow opposition parties—especially UNM politicians—hijack the protests is an indicator that the UNM lacks citizens’ trust.[8] This is why protesters have assumed, and perhaps rightly so, “that seeing the party leaders in charge of protests could reduce mobilization.”[9]

On the other hand, it is understandable why the UNM and/or EG may want to have ownership on Russia as an issue in Georgian political discourse. Georgia experienced a brief war with Russia in August 2008 and a range of economic sanctions from Russia under their rule. Furthermore, as the protests have shown, Russia as an issue resonates with the Georgian public. Therefore, winning over this large part of the electorate is attractive for any political party. On the other hand, the GD’s reluctance to emphasize Georgia’s relations with Russia as a significant issue for party competition is equally understandable. Since 2012, when the GD first came to power, the government has been trying to normalize relations with Moscow—a policy that led to creating a special format of Georgian-Russian talks, during which the two sides discuss economic and trade-related issues as well as people-to-people contacts. In this framework, Georgia and Russia restored trade relations and facilitated travel between the two countries[10] —the very achievements that are endangered after the recent ban of Moscow on flights between the two countries and the import of Georgian wine to Russia.[11]

As a result, the UNM was allowed by other political parties to try and take ownership of Russia as an issue in Georgian party competition. The public, however, appears unconvinced that voters need to follow the UNM or EG on this matter regardless of how these parties and their leaders are perceived.

What lessons can Georgian parties learn from these developments?

There are a few ways parties can compete against each other. Establishing ownership over specific issues can be one of them. However, that does not always work, especially against the background of decreasing public trust in political parties. Therefore, Georgian parties need to reflect on such developments and adjust to meet the demands of voters in order to propose appealing policies. For example, parties can offer distinct positions on a range of issues, which currently is limited to two policy issues—integration in NATO and the role of government in maintaining law and order—and in both cases it is the APG that differs from the GD and UNM. Furthermore, parties should focus on more meaningful policy areas that are of public concern or interest, e.g. the economy and social welfare. Finally, parties should focus on increasing public trust in them. The June protests are not the first example of this; the same tendency was present in 2018.[12] If parties indeed draw these lessons[13] and internalize them, Georgian politics will become more responsive toward voter preferences and the public will no longer be as disappointed with political leaders as it is today.

Levan Kakhishvili is a Policy Analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) and a Doctoral Fellow at Bamberg Graduate School of Social Sciences (BAGSS) at the University of Bamberg, Germany, funded by DAAD GSSP scholarship. His doctoral research is about how political parties compete in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine.

[2] Civil Georgia. (2019). Opposition, Civic Activists Gather to Protest Russian Delegation’s Visit to Tbilisi. [online]. Available at: https://civil.ge/archives/309241

[3] Civil Georgia. (2019). Update: Protest Ends, Activists Demand Interior Minister’s Resignation. Available at: https://civil.ge/archives/309840

[4] Civil Georgia. (2019). Ivanishvili: 2020 Polls Proportional, Zero Threshold [detailed text]. [online]. Available at: https://civil.ge/archives/310307

[5] All analysis involving party manifestos has been conducted by the author using a content analysis method and a coding strategy developed for the Comparative Manifesto Project (see: Budge, I. (1987). The internal analysis of election programs. In I. Budge, D. Robertson, and D. J. Hearl (eds.), Ideology, strategy and party change: Spatial analyses of party programs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.). The author has introduced a minor modification to the coding strategy and coding categories to reflect local nuances of Georgian party politics.

[6] A new party, European Georgia (EG), did not exist at the time of the 2016 elections, which is why, in this article, EG is excluded from most analysis.

[7] A party created out of the UNM’s ranks after the 2016 parliamentary elections, which is why EG is often framed as an extension of UNM. Furthermore, EG and UNM have similar positioning toward Russia.

[8] On issues related to trust in political parties in Georgia, see: Kakhishvili, L. (2019). Decreasing level of trust in Georgian political parties: What does it mean for democracy and how to avoid negative consequences? Georgian Institute of Politics [online]. Available at: https://gip.ge/decreasing-level-of-trust-in-georgian-political-parties-what-does-it-mean-for-democracy-and-how-to-avoid-negative-consequences/

[9] Tsutskiridze, L. (2019). Protest in need of strategy. Civil Georgia [online]. Available at: https://civil.ge/archives/310088

[10] For a comparative analysis on the UNM’s and GD’s policies and discourse toward Russia, see: Kakachia, K., S. Minesashvili, and L. Kakhishvili. (2018). Change and continuity in the foreign policies of small states: Elite perceptions and Georgia’s foreign policy towards Russia. Europe-Asia Studies, 70(5), 814-831.

[11] Jonas, T. (2019). Russian Soft Power Fails, Pointing the Way to a New Georgian Consensus. Civil Georgia [online]. Available at: https://civil.ge/archives/310329

[12] See: Batumelebi. (2018). რას და როგორ აპროტესტებენ საქართველოში – ინტერვიუ პოლიტოლოგთან. [online]. Available at: https://batumelebi.netgazeti.ge/news/142788/

[13] On how these lessons can be translated into actions from the side of political parties, see compendiums of policy briefs published annually by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP). Available at: https://gip.ge/publications/books/

[online]