In the context of democratization and democratic consolidation, internal political crises, caused by either external shocks or dynamics in the domestic arena, pose a significant challenge to the stability of the Georgian political system. Such crises can jeopardize not only internal order but also Georgia’s relations with external actors. However, one of the latest crises, the June 20 and the following protests, linked the external and internal dimensions of Georgian politics. The protest wave started on June 20 as a result of a Russian MP from the Communist Party, Sergei Gavrilov, addressing the delegates of the Inter-parliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (IAO) in Russian from the seat of the speaker of the Georgian parliament. Although the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party made some concessions, the major promise, proportional elections, has not been fulfilled. On November 14, the parliament voted down the constitutional amendment on transition to proportional system from 2020, which indicates that the political crisis has not yet been resolved. On the other hand, the representatives of the ruling party for a few weeks of June and July tried to construct a narrative with their statements that tried to convince the Georgian public why they should not view the protests favorably. This blog explores the anatomy of the GD narrative and argues that it has not been successful in convincing the public. Considering that the GD has not delivered on their promise, the public already feels highly disappointed and protests resume in front of the parliament. Consequently, the GD will need a much stronger justification and a more constructive language to persuade voters in quitting protests. This will need to be coupled with specific actions delivering tangible results.

The Gavrilov incident: An “outrageous mistake”

The June crisis consists of two major parts: the Gavrilov incident per se on June 20, followed by the use of force during the dispersion of the rally in front of the parliament the night of June 20. The latter escalated the situation and led to further demonstrations.

During the initial part of the crises, before the police use of force, three main patterns emerged in the public statements made by GD officials: admitting guilt, denying guilt and shifting guilt. Notably, admitting guilt was the dominating communication strategy while the ruling party tried to make meaning out of the Gavrilov incident and communicate it to the public. However, at a later stage, GD representatives, including the chairperson of the party, Bidzina Ivanishvili, tried to either downplay the symbolic importance of the incident or completely deny the ruling party’s guilt.

While admitting guilt, GD politicians tried to label the Gavrilov incident as a “mistake” or a “protocol blunder,” which was “unacceptable” and the “hardest thing to watch,” resulting in the “sincere outrage” of the Georgian public. For example, Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze stated on June 20: “An outrageous mistake has taken place … [Organizers of the IAO] will have to apologize and explain the Georgian society what has happened and why.” Such a narrative was actively developed by GD representatives during the first days following the June events. On the other hand, there were some cases of denying or shifting the guilt. For example, Irakli Kobakhidze, the now former speaker of the parliament and President Salome Zurabishvili both tried to emphasize Russia’s role as a country that has occupied Georgian territories and whose actions has nothing to do with Christianity or Orthodoxy other than using the religion as a political instrument. On the other hand, at times GD representatives would stress that Gavrilov’s chairing the session was not agreed with the Georgian party or that the event was “unforeseeable” and “unavoidable.” Later, on July 17, however, Bidzina Ivanishvili weighed in and argued that although public concerns were “fair,” Gavrilov’s visit was neither important nor a crime and that the “hype” was created by none other than United National Movement (UNM) over a small “protocol mistake.”

The use of force: An attempted coup?

The peak of the first part and also a turning point of the crisis was the night of June 20. During the night, the police used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the demonstration in front of the parliament. This, instead of terminating the crisis, triggered a new one, which manifested itself into a prolonged wave of protests, about which the ruling party had to create a new narrative.

Various narratives emerged following the night of June 20. The narratives followed two main directions: first, justifying the use of force during the night of June 20; and second, blaming the domestic actors fort not only the night of June 20 but also the aftermath.

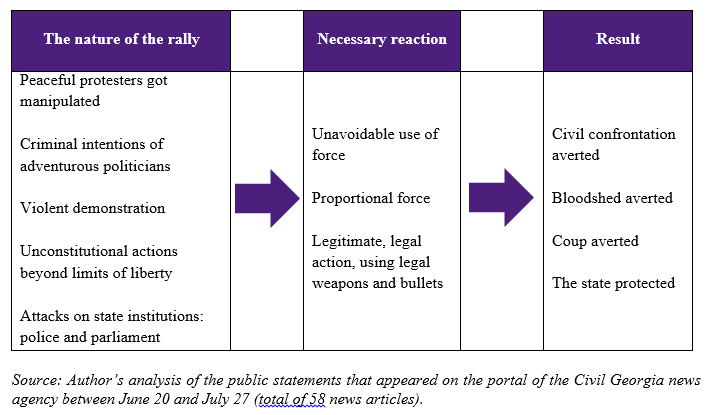

The ruling party representatives constructed a narrative about the night of June 20 around three major elements: a description of the context, i.e. the nature of the rally; the police’s adequate response, i.e. the use of force; and the result (see Table 1). Overall, the goal of the narrative was to convince the public that the demonstration was violent and the UNM was guilty of manipulating peaceful protesters; that the use of force was not only legitimate and proportional but also unavoidable; and that the result was the police averted civil confrontation, bloodshed, and a coup d’état.

Table 1: The GD narrative about the night of June 20.

The aftermath: Responsible youth or UNM’s stooges?

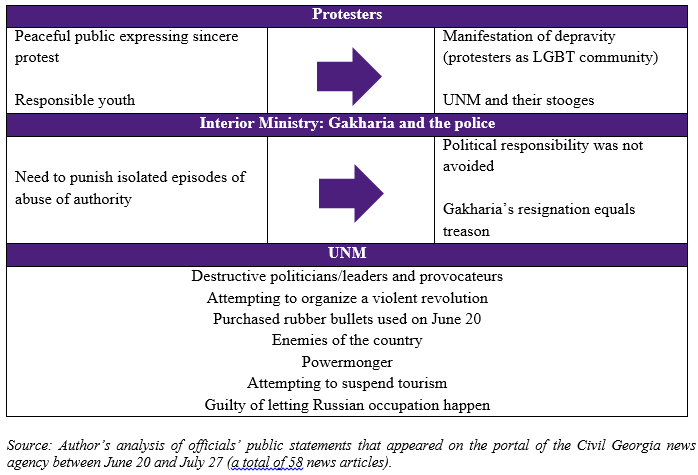

When it comes to describing the domestic actors involved in the June protests, the GD narrative turns out to be dynamic, meaning that after about a week of protests, GD started to change the way they talked about the main actors in the process. This shifted rhetoric was solidified with time. Three actors can be identified: the protesters, UNM, and Interior Ministry, i.e. the police and minister himself, Giorgi Gakharia. However, only references to UNM remained constant in the government’s messages over the course of the month following the protests of June 20. The authorities’ narratives about the protesters changed from more positive to more negative over time, while references to the Interior Ministry changed from mildly critical to highly commendable (see Table 2).

Table 2: Portrayal of domestic actors involved in June events according to ruling party’s dynamic narrative.

Conclusion: Are people convinced?

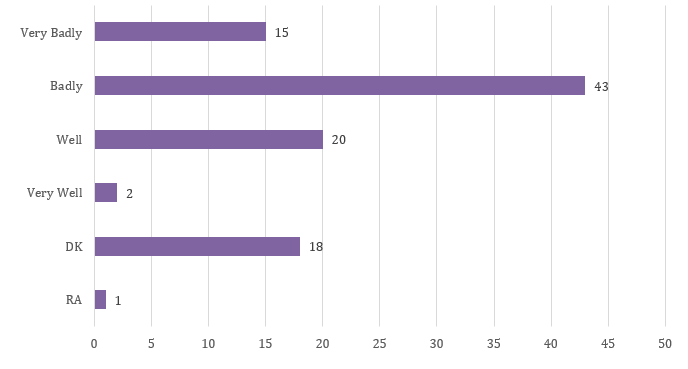

Overall, GD officials have demonstrated solid, coordinated action to construct a narrative downgrading the importance of the Gavrilov incident, justifying the use of force during the night of June 20, and demonizing the domestic actors involved in the aftermath protests. On the surface, the coordination of strategic communication looks impressive. But it does not indicate the extent to which the government’s narrative convinced the public. In fact according to data from an NDI opinion poll conducted in July 2019, 58 percent of the surveyed respondents evaluated the government’s response to the June protests as “badly” or “very badly”, while the share of positive evaluations of “well” and “very well” amounted to 22 percent (see figure 1). At the same time the share of respondents who could not answer the question was 19 percent.

Figure 1: Evaluation of government’s response to the events of June 20 and the following protests (%)

What these figures show is that the public is dissatisfied with how the government has managed the June crisis and the numbers should be alarming for the ruling party. This means that Georgian voters will not remain calm and to manage this high amount of dissatisfaction, the GD will need to invite the leaders of the protests to negotiation tables for the very least. Additionally, if GD wants to save the face, they will need a better narrative to ensure that the public anger is properly managed, and situation is not further escalated. In this context it is important to adopt constructive language and, more importantly, take action to deliver tangible results in order to resolve the political crisis triggered by a range of decisions that were not thought trough properly.

Levan Kakhishvili is a policy analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP).