Authors

Dennis Redeker and Sebastian Kuhnke

Georgia’s 26 October 2024 parliamentary elections are not just another political contest in the country’s evolving democratic journey; it is a decisive moment that will determine the nation’s geopolitical orientation for years to come. At its core, the elections represent a choice between continuing Georgia’s long-standing ambition to integrate with Western institutions like the European Union and NATO or embracing a more authoritarian-leaning future, often linked with closer ties to Russia. This crossroads is not new for Georgia, a country that has long been balancing between East and West. However, the events of the past few years—particularly the passage of the “Law on Transparency of Foreign Influence”—have highlighted the stakes involved and brought the question of Western alignment to the forefront of the national debate.

The importance of these elections cannot be overstated. Since the early 2000s, Georgia has consistently pursued integration with Euro-Atlantic institutions, seeing membership in the EU and NATO as not only as a haven for security and economic integration, but also as a pathway to deeper political and economic reforms.

However, recent actions by the ruling Georgian Dream party and its allies in parliament, particularly the reintroduction of the controversial “foreign agents bill”, have cast doubt on the country’s Western trajectory.

The law, which mirrors similar legislation in Russia, requires non-governmental organizations (NGOs) receiving more than 20 percent of their funding from abroad to register as “foreign agents.” It has been widely criticized as an attempt to stifle civil society and weaken pro-democratic forces in the country.

Once introduced and then withdrawn in 2023, the law’s introduction and subsequent passage in 2024 sparked widespread protests, with thousands of Georgians taking to the streets in opposition. These protests were not just about the law itself but about what it represents—a move away from Georgia’s democratic aspirations and a potential realignment toward Russia’s sphere of influence. The law is seen by many as part of a broader effort by the Georgian Dream government to consolidate power ahead of the upcoming elections by weakening opposition groups and civil society, both of which are crucial supporters of Georgia’s Western orientation.

At the heart of this debate is the issue of trust.

Public opinion surveys consistently show that Georgians place more trust in Western institutions like the EU and NATO than in their own government or NGOs.

Despite this, the Georgian Dream government has sought to position itself as the defender of national sovereignty, accusing NGOs and pro-Western forces of being agents of foreign interference, even portraying them as (themselves manipulated) war-mongers (connected to a “Global War Party”). This narrative has resonated with some segments of the population, particularly those who are more skeptical of Western influence and view NGOs as being disconnected from everyday Georgian concerns. It does not help that NGOs in Georgia are indeed heavily financed by Western state and non-state sources, rather than being based on domestic funds such as donations and private foundations.

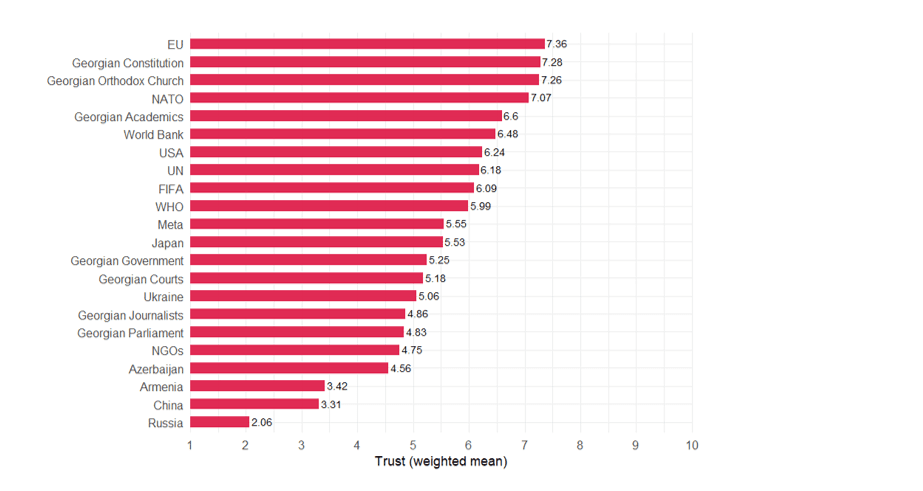

With a recent study, we contributed to the existing public opinion research in Georgia by fielding new questions and scales to better understand trust in institutions and actors, including other nation-states. The study, which has not been peer-reviewed yet, has been conducted in December 2023 with the aim to foster our understanding of political dynamics in Georgia, adding to excellent work done by people at inter alia the Caucasus Barometer, the National Democratic Institute (NDI) and the International Republican Institute (IRI). The results are based on 1,091 valid responses, thought to represent the population of Georgia well. The dataset has been sampled using social media-based recruitment via Facebook, a social media platform almost used universally in Georgia. Respondents were asked about their trust in 22 different institutions and (international) actors and weighted the responses, displayed in the Figure below. Respondents were able to choose on a scale between no trust at all (1) and very high trust (10).

Importantly, our data shows that as of December 2023, the Georgian Constitution and the Georgian Orthodox Church enjoy the highest levels of trust among domestic institutions. On the other hand, trust in NGOs and the Georgian government is significantly lower. Among international actors, Russia has the lowest trust score, followed by China and Armenia, while the EU stands out with the highest trust level. The US, the UN and NATO rank relatively high. Overall, the positive sentiments toward the EU and the West at large, as found in previous surveys, are mirrored in our data. Only 14 percent of respondents distrust the EU (trust of 1-3 points), only 23 percent distrust the US. However, the current government and NGOs are each distrusted by 38 percent of respondents, Russia is even distrusted by 83 percent of respondents.

These findings lead us to conclude that, apart from the Georgian constitution and church—and maybe Mgzavrebi—the only shared trust in this polarized time for Georgia appears to be in the West, the European Union in particular. Under these circumstances, it is difficult to imagine how a government that cuts Georgia’s ties to the West—and faces sanctions by its partners in return—is to function with internal peace and how it can rally its people behind an alternative vision for the future.

___________________________________________________

Dr. Redeker is a political scientist at ZeMKI Centre for Media, Communication and Information Research, at the University of Bremen;

Mr. Kuhnke is a graduate student of political science at the University of Bremen. Funding for data collection came from the Academy of Humanities and Sciences in Hamburg.