Author

Givi Silagadze

Georgia’s polarized political landscape has been shaken by a newcomer—Mamuka Khazaradze. His entrance to politics coupled with a promised transition from a mixed electoral system to a fully proportional one has generated a great deal of interest in Georgian society as well as in the media. Experts and journalists, speculating on the possible political formations that could appear following the 2020 elections, are asking whether Mamuka Khazaradze’s forthcoming party will succeed in attracting votes and whether it will emerge as a viable alternative in Georgia’s bipolar politics. Although there are no straightforward answers to these questions, it is argued throughout this blog that Mamuka Khazaradze and his forthcoming party might be relatively well-positioned to challenge the bipolar pattern and emerge as a solid political actor in the Georgian politics.

Entrance to Politics

Khazaradze underlined the June 20-21 violence and “an intentional process of splitting and confronting our [Georgian] society” as a trigger for his entrance into politics. However, there is background to this story, which arguably played an important role in Khazaradze’s political activation. Developments that supposedly pushed Khazaradze to enter politics are related to the recent investigation launched against Mamuka Khazaradze and his partner Badri Japaridze concerning alleged money laundering committed ten years ago. This investigation has raised suspicions among civil society organizations and Khazaradze has explicitly blamed the government for acting against the strategically important deep-sea Anaklia port, the construction of which was supposed to be undertaken by Anaklia Development Consortium (ADC). A holding group founded by Khazaradze, TBC Holding, and its partners created the ADC. This has led political observers to speculate about a personal confrontation between Bidzina Ivanishvili and Mamuka Khazaradze, arguing that Khazaradze did not challenge Ivanishvili until the former PM “forced him out of his comfort zone.” Consequently, Khazaradze is poised to challenge to the existing political order.

What Could Impede Khazaradze’s Political Success?

Mamuka Khazaradze’s movement might not be perfectly positioned to gain outright widespread support from voters. Particularly, two points are worth discussing: a “why now” argument pointing to Khazaradze’s political passivity in the past; and Khazaradze’s background as a top banker in a country where a large part of society is poor and harbors a high level of distrust towards commercial banks.

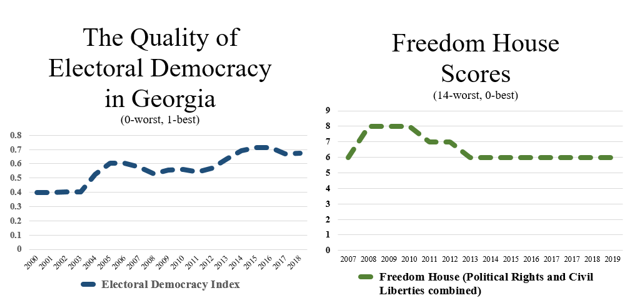

Khazaradze’s history of political inaction might not benefit his political plans. It is convenient for Khazaradze’s political foes from the opposition as well as from the ruling party to point to his past, as he did not explicitly express his concerns towards earlier undemocratic and detrimental developments. Such critics might have a point—according to international reports, the quality of democracy in Georgia had been worse in the past, especially during the period from 2007 until 2012 (see Figure 1). Furthermore, police violence during the June 20 anti-government demonstration, which Khazaradze referred to as “a red line,” is not unprecedented in Georgia. In 2007 as well as in 2011, the previous government used violent force against protesters.

Figure 1- The quality of democracy in Georgia

Source: The Electoral Democracy Index is taken from the Varieties of Democracy Project (see the link: https://www.v-dem.net/en/analysis/CountryGraph/).

Freedom House Scores are taken from Freedom House reports (see the link: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2019/georgia)

These circumstances might encourage Khazaradze’s opponents to question his motivation for creating a new party and seek to portray his political career as insurance for his business interests and as a means to secure personal safety. Indeed, high-ranking Georgian officials have already stated, alluding to Khazaradze, that “a political party is not an indulgence.” Therefore, Mamuka Khazaradze will probably have to wrestle with a range of questions regarding his political passivity in the past and his true motivation for entering politics now.

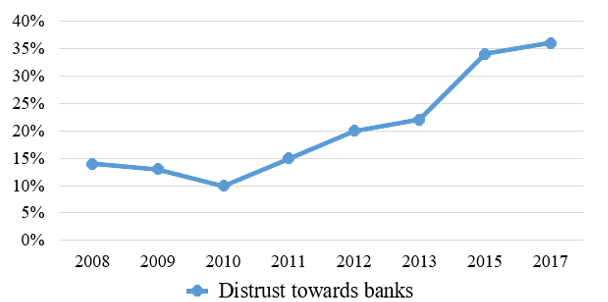

Another important stumbling block to Khazaradze’s political success might be that he is a banker and, in a country with pressing problems of poverty and non-performing loans, being a top banker is not an asset for a successful political career. Distrust towards banks in Georgia has been growing recently (see Figure 2). Khazaradze’s image is intertwined with the banking sector, which might offer fertile ground for attacks from socially-minded young leftist activists as well as from politicians intending to exploit the extremely poor economic conditions of a huge part of the Georgian society. Throughout 2018, banks were a popular target for almost the entire political elite. Saakashvili has harshly criticized banks and accused them of implementing “anti-Georgian” policies. In a similar vein, Bidzina Ivanishvili has named loans as a major cause of poverty in Georgia. During the 2018 presidential campaigns, then Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze announced that Ivanishvili’s foundation would cover the debts of more than 600,000 people. However, Khazaradze has recently argued that the burden of writing off debts was primarily placed on banks rather than on any foundation. Consequently, Khazaradze has to find a way to overcome Georgians’ widespread negative attitudes towards bankers and banks or risk the chance that his political enemies will capitalize on it.

Figure 2- Growing distrust towards banks in Georgia

Source: The data is taken from Caucasus Research Resource Center’s “Caucasus Barometer time-series dataset”.

Why Khazaradze is well-positioned?

Despite the impediments, a number of circumstances indicates that Khazaradze might be well-positioned vis-à-vis previous challengers of the bipolar nature of Georgian politics. In this regard, a comparison can be made with Paata Burchuladze and his party, State for the People, which campaigned for the 2016 parliamentary elections. Despite its initial favorability, the party of the famous opera singer-turned-politician failed to defy the bipolar structure and enter parliament. Although there are similarities, three factors set Khazaradze apart: his image as a person able to lead a highly successful business career in unstable conditions; his declared defiance of bipolar politics; and the increasing negative public attitudes about how Georgia is developing.

Although newcomers to politics, both Burchuladze and Khazaradze are well-known in Georgia as well as abroad, which is an asset in politics as it is not necessary to make a huge effort to raise visibility in public and almost by default the media is interested in them. Additionally, Khazaradze as well as Burchuladze have the capacity to secure financial resources; during the 2016 electoral campaign, only the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party spent more than Burchuladze’s State for the People. Similarly, it is unlikely that Khazaradze will struggle to channel financial resources towards his political organization. However, none of them can be compared with financial sustainability of the ruling party: Burchuladze’s party encountered financial problems during the final phase of 2016 campaign. Regarding Khazaradze, the Prosecutor’s Office froze his financial assets recently, which might complicate his task. That means money is important and it will be very difficult to succeed in Georgian politics without financial sustainability.

On the other hand, the backgrounds of the two figures are different: Paata Burchuladze is a famous opera singer and philanthropist while Mamuka Khazaradze is primarily associated with a leading bank in Georgia. Even though his association with the banking sector will probably impede Khazaradze’s political ascent, for some voters Khazaradze is a person who managed to construct a highly successful structure in the deeply unstable social and political environment that defined Georgia in the 1990s.

Moreover, even though little is known about Khazaradze’s future plans, his cooperation strategies are arguably different than those of Burchuladze. While Khazaradze has explicitly stated that he will not cooperate with Bidzina Ivanishvili, Mikheil Saakashvili or the political forces associated with them, Burchuladze leaned towards one pole of the polarized political landscape: his party formed a coalition with other political forces formerly associated with United National Movement (UNM) and currently is in a coalition with UNM. Khazaradze, on the other hand, has been attacked from both sides of the Georgian politics, which is not unexpected given the nature of the extremely polarized environment. Furthermore, as Khazaradze declared, his forthcoming political party will not involve famous politicians, which might be a smart move due to high public disappointment with politicians. However, this step has its downsides as it might prove difficult to recruit a sufficient number of people that are politically “sterile” and experienced at the same time. Therefore, Khazaradze’s starting position is better and he can learn from the example of State for the People.

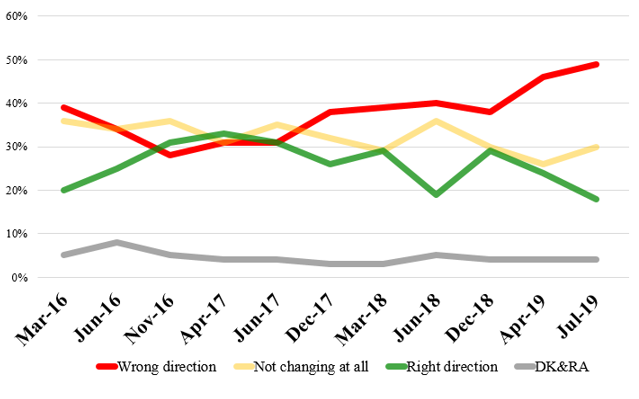

Figure 3 – Which direction is Georgia going in?

Source: Caucasus Research Resource Center. A set of datasets “NDI: Public attitudes in Georgia”.

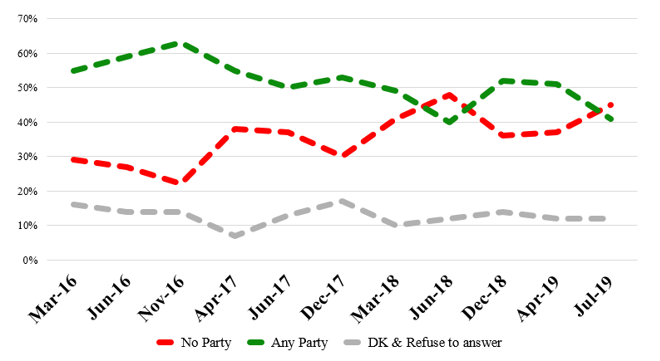

Finally, the context seems more favorable for a newcomer in 2019 than it was in 2016 when Burchuladze entered politics. Today, more people think that Georgia is going in the wrong direction than in 2016 (see Figure 3). Furthermore, the number of people who do not identify with any party and could not name one political organization to which they feel closest has been growing since 2016 (see Figure 4). Accordingly, Khazaradze is in a better position to gain support and challenge the existing political structure. In parallel with the growing dissatisfaction with Georgia’s development, an increasing number of people feel disconnected from the existing political organizations. This means that the growing dissatisfaction of voters does not translate into support for existing oppositional parties, which increases the chances that a potential third force can attract votes.

Figure 4 – Party identification since 2016

Source: Caucasus Research Resource Center. A set of datasets “NDI: Public attitudes in Georgia”.

Concluding Remarks

The starting position of Mamuka Khazaradze’s movement to defy the bipolar political competition between GD and UNM is better than that of any previous challenger. He has financial resources, which is an important condition for gaining success in Georgian politics. Additionally, he has experience creating an efficient structure, such as TBC Bank, which might assist him to build a well-functioning political organization, especially in the regions. Furthermore, he publicly disapproves of affiliation with any of the two poles (UNM/GD), suggesting that it is unlikely he will conform to bipolar politics.

Furthermore, there are structural factors that benefit Khazaradze’s political plans. Particularly, the 2020 parliamentary elections will probably be held through a fully proportional electoral system without a formal threshold, which is more permissive for any party that challenges the bipolar pattern than the existing mixed system. Moreover, the public’s skepticism about Georgia’s direction of development and disconnection from the existing political parties are peaking. These factors suggest that Khazaradze might be well-positioned to become a third alternative in the Georgian politics.

However, it is difficult to be certain about the prospects of Khazaradze’s political career. In politics, there are always unpredictable developments. He has to come up with a clear overall electoral platform and policies, surround himself with reliable partners and overcome Georgians’ negative sentiments towards bankers and banks. To achieve his goal he has to assemble a team consisting of politically “sterile” but experienced people and run a successful pre-election campaign. This might be an extremely demanding job.

*Givi Silagadze is a Junior Policy Analyst at the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP).