Levan Kakhishvili, Elene Panchulidze

Despite the fact that European integration is a priority for the Georgian government, public opinion polls demonstrate that there is a lack of public awareness about the processes of Europeanization and democratization. It is not always clear to an average Georgian whether these two processes are the same or completely independent from each other; what each of them implies and whether they are imposed by outside forces or nurtured from within Georgian society. A part of the problem is that Georgian civil society is highly concentrated in Tbilisi. One can argue that most if not all discussions, conferences, roundtables, etc. are attended by the same people over and over again. While this has created a closed circle of people who are relatively more aware of Georgia’s path of development, it has not resulted in the efficient spread of information to the wider society – average Georgians for whom DCFTA does not mean much in their daily lives. If the Georgian government aims to consolidate support for Georgia’s democracy and European aspirations, it is extremely important that everyone in Georgian society is engaged in the process, especially those who are currently not involved in the discussion.

Support for democracy, EU and NATO

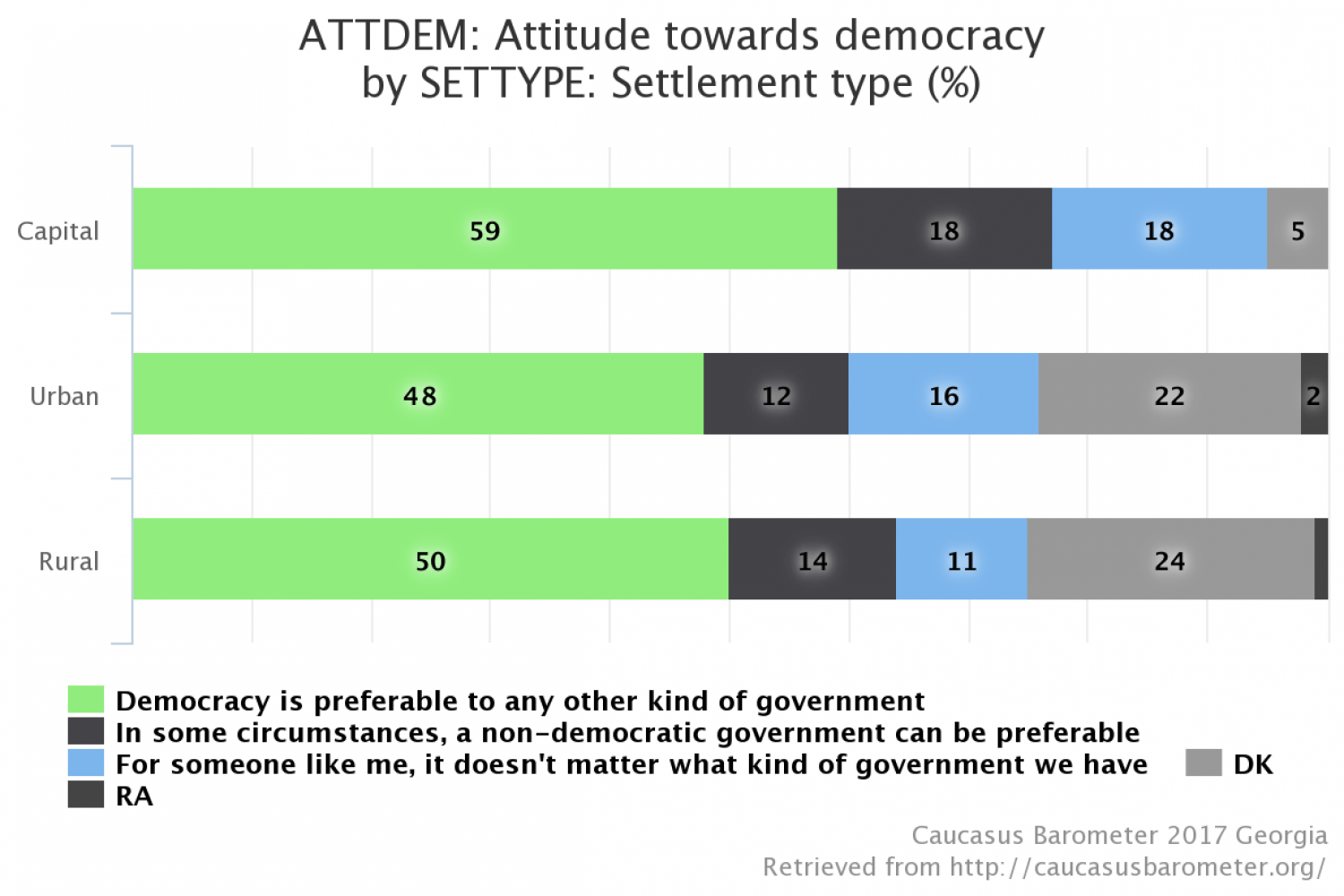

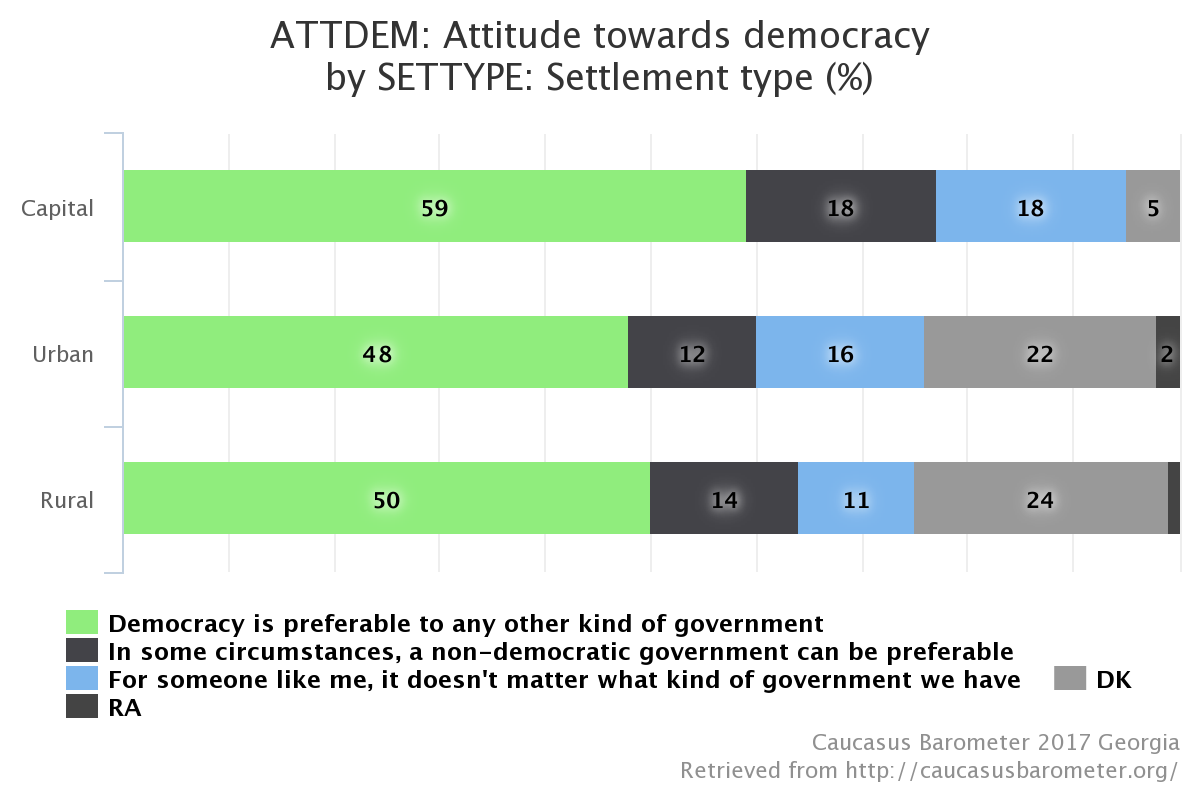

Support for democracy in Georgia falls short of an overwhelming majority: for the past few years, only about half of the population prefers democracy to any other type of government. The degree of support has been declining and it is important to note that support levels are lower outside Tbilisi. According to the 2017 Caucasus Barometer data,[3] while 59 percent supports democracy in the capital, the figure drops 9 percentage points for rural areas and 11 percentage points for other urban areas (see chart 1).

Chart 1: Support for democracy in Georgia by settlement type

What is interesting about the data in Chart 1 is that the number of people who said they did not know the answer to the question or refused to respond is five times higher outside the capital and constitutes every fourth person living in the regions of Georgia. This indicates that information is not efficiently channeled to citizens living outside of Tbilisi.

A similar story emerges when public support for Georgia’s membership in the EU and NATO is examined. According to the same survey, the number of undecided respondents concerning both EU and NATO membership was three to six points higher outside the capital than in Tbilisi. In urban areas, the number of undecided respondents was 12 and 13 percent for the EU and NATO respectively, while in rural areas the figures stood at 18 and 19 percent respectively.

Potential causes and challenges

Several major issues became apparent when the authors of this report held public discussions in four Georgian cities: Batumi, Gori, Kutaisi, and Telavi. In addition to the inherent challenges facing information campaigns and outreach managed from the capital, the discussion participants lacked information about the differences between Europeanization and democratization as well as the varieties of democracy worldwide. Agents of these processes (e.g. political parties and NGOs) also demonstrated a lack of awareness about democratization and Europeanization. In addition, the public showed distrust towards, frustration with and fear of political participation and finally materialistic political culture in Georgia.

Europeanization vis-à-vis democratization

Participants in discussions in the regions of Georgia often argued that Europeanization is not the same as democratization and, as a result, two questions emerge. First, considering the democratic fatigue of countries such as Hungary and the events of Brexit referendum, what if Georgia is heading to the place from which other countries are fleeing? Second, what if Georgians do not want a Western-style liberal democracy and would rather live in a type of democracy similar to that of Japan, which coincidentally is a society that highly values its own cultural traditions? Of course these questions can be easily answered by explaining what led to Brexit and why Hungary is backsliding, and by focusing on how much more the EU is than these two cases. It is also relatively straightforward to show the differences between different types of democracies. The fact that these questions are asked in the regions and not in Tbilisi might mean one of two things: either regions in Georgia lack information about these issues or they do not intend to accept any offer without first questioning it, discussing publicly and coming up with a consensual decision. The first option presents an obvious challenge. If the questions coming from rural Georgian society actually mean that people want to discuss the issues, however, that is a positive sign for the Georgian political culture.

Agents of democratization and their flawed nature

Another recurring idea voiced during discussions was that the agents that are supposed to contribute to the processes of democratization and Europeanization, including Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) and political parties, are not fully informed about the two processes and what they imply. In addition, both CSOs and political parties are not viewed as credible sources of information by the wider population. There is a high level of distrust towards CSOs as they were often seen by participants as politicized, polarized, self-righteous entities that speak in the name of all people. On the other hand, political parties were characterized as unstable due to the lack of coherent ideologies, and nontransparent practices when nominating candidates or selecting a chairperson. According to participants, if these agents do not address their flaws, it is highly unlikely that Georgia can become a democracy. To this end, political parties and CSOs need to engage with local communities in a more active and transparent manner and create the product that express clear and direct benefits for local communities.

Distrust, frustration and fear

Political participation is an important aspect of democracy and an active society is a crucial part of that process. The words people used during the discussion to describe political participation indicated there are serious challenges in this area, however. More often than not, participants would speak of distrust, frustration and fear when discussing political participation. Based on their word choice, it appears that the public seems to distrust political institutions, decision makers, and agents such as parties and CSOs. In general, a high level of distrust towards the motives of those who are actively engaged in the process exists, which undermines any wider public interest in participating. Furthermore, participants repeatedly stated that being politically and socially active does not really yield results. Participation was often viewed as a pointless and futile activity since it does not appear to impact decision-makers’ actions. Finally, participants also expressed fear about engaging in political activism. It seems that a significant number of people are wary of political activism and fear it will lead to negative consequences for themselves or their families. The existence of these concerns is harmful for the development of grassroots civil society and for people to enjoy the benefits of democracy.

Materialistic political culture

According to public opinion polls, since 2009 the public has named socio-economic problems and unemployment in the top three domestic problems facing the country. Therefore, understanding the rationale behind current public perceptions is not very difficult: personal income is more important than abstract indicators of GDP or democracy. It is difficult to think about democracy and the development of institutions when citizens are unable to meet their basic needs. It is illustrative that the one question participants posed was the choice between being “hungry” and living in a democratic country and being “well-fed” and living in an authoritarian country. This is exactly why participants believed Georgian voters sell their votes during elections for as low as 10 GEL. However, this is a false dilemma; a democracy does not have to be socio-economically under-developed. Although it is widely accepted that democracies are not necessarily economically more efficient than authoritarian regimes, they certainly do not have to be poor. Again, in this regard, active and efficient communication and awareness rising is needed in order to completely and convincingly respond to the questions being raised by the rural population.

Conclusion

This discussion shows that while Tbilisi is often viewed as representative of the entire country, there is more to Georgia than the capital. In fact, public opinion varies across the country and depends on whether one looks at Tbilisi, other urban areas or rural settlements. Moreover, public opinion polls show that the number of people who cannot make up their mind on important national issues, such as Georgia’s democratization and Europeanization, is several times higher in the regions compared to the capital. The same conclusion was supported by the discussions conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics in Batumi, Gori, Kutaisi, and Telavi. Participants of the discussions spoke about a range of topics. Their responses showed the need for intensive work by the government, media and civil society actors to reach average Georgians who are likely living in an informational vacuum that is physically and mentally far from all the discussions, conferences, workshops and roundtables organized in Tbilisi.

- The report is prepared on the basis of discussions conducted in the framework of the project “Georgia at the Nexus of Democratization and Europeanization;” representatives of academia, media outlets, local authorities, political parties and CSOs participated in discussions. The project is implemented by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) with the financial support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED).

- Levan Kakhishvili and Elene Panchulidze are policy analysts at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP).