© Originally Published by Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich

© Cover Photo: Johnny Harris

Abstract:

This article examines Georgia’s foreign policy trajectory following the recent parliamentary elections and its implications for Russian-Georgian relations. It delves into the challenges Georgia faces as a small state strategically positioned between the European Union and Russia, navigating the delicate balance between its aspirations for Euro-Atlantic integration and the reality of Russian influence. The analysis highlights how domestic political developments, including the lack of internal and external legitimacy of a one-party-dominated parliament, have weakened Georgia’s socio-economic and institutional resilience. These vulnerabilities leave the country susceptible to external pressures, particularly from Moscow, which seeks to leverage divisions within Georgian society to reinforce its influence.

The controversial 2024 parliamentary elections in Georgia have further complicated the country’s foreign policy trajectory. The election was broadly regarded as a referendum on Georgia’s geopolitical future and was therefore dominated by foreign policy concerns, eclipsing traditional domestic issues. Whereas the opposition framed the elections as a choice between Europe and Russia, the Georgian Dream (GD) government portrayed them as a choice between war and peace, claiming an opposition victory would drag Georgia into another war with Russia. Civil society, meanwhile, saw the choice as being between democracy and Russian-style authoritarianism.

The ruling party, Georgian Dream (GD), announced a narrow majority(CEC ,2024) victory in the election, but the outcome was marred by controversy.

Nearly all opposition parties have refused to accept the results reported by the election authorities, declining to enter the new parliament and demanding fresh elections, as well as calling on Georgia’s Western partners to conduct an international investigation into alleged electoral misconduct.

As the opposition raised concerns over alleged irregularities, including voter intimidation and procedural manipulation, Georgian president Salome Zurabishvili stated that the country had been the victim of a “Russian special operation”.(RFL/RL, 2024). Moscow denied the allegations, accused the West of interfering in Georgia’s internal affairs, and expressed readiness to further normalize bilateral relations with Georgia.

Although international observers, including the OSCE, reported that the election’s transparency fell short of democratic standards, prompting calls for an investigation from U.S. and EU leaders, Russia and a handful of other countries—Azerbaijan, Iran, Armenia, China, Türkiye, and Hungary—endorsed the results. The Georgian Dream-led government, which promotes closer ties with Moscow, still hopes to reset relations with the West. However, it remains isolated, lacking both internal and external legitimacy. This situation has raised significant questions about the future of bilateral relations between Russia and Georgia.

Georgian Dream’s Geopolitics: Between War and Peace

A contested election may cement Tbilisi’s drift away from the West, leaving Georgia facing isolation both domestically and internationally. While the Georgian Dream-led government continues to deepen its ideological and geopolitical alignment with Russia, there are critical questions about the extent to which Georgia can accommodate Russia’s strategic interests without compromising its own sovereignty and territorial integrity.

This issue was a major topic of discussion during the pre-election period. By invoking memories of past conflicts with Russia, GD emphasized its commitment to preserving peace and strategically leveraged the “Russian factor” during the campaign to bolster its position and portray itself as the force most capable of preventing renewed hostilities. It framed the election as a critical choice between stability and security under its leadership, on the one hand, and potential disorder under the opposition, on the other hand. Additionally, GD made several pointed statements regarding South Ossetia and Abkhazia, hinting at a potential opportunity to restore long-awaited territorial integrity and even claiming that the party was prepared to risk Western sanctions in pursuit of the country’s “reunification.” Ivanishvili’s controversial Gori speech, which many interpreted as blaming Georgia for the 2008 war rather than Russia, only fueled these allegations. The party’s Political Council even highlighted the necessity of readiness for peaceful territorial reintegration, stating that “given the rapidly evolving situation around Georgia, we must be prepared to restore territorial integrity in a peaceful manner and be ready for such a scenario at any time.”[1] This included the possibility of constitutional amendments to adapt Georgia’s governance and territorial arrangements to new realities. While, after a 50-day delay, Georgian Dream has finally denied claims that they are considering a confederate state with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the ruling party’s growing rapprochement with Russia was increasingly framed as a conduit to achieving this goal.

Moreover, such statements were widely seen as signals that Moscow was prepared to help Tbilisi restore relations with the breakaway regions—a narrative that clearly worked to the advantage of Georgian Dream. Russian officials have acknowledged Ivanishvili’s apology as a positive shift in Georgia’s stance on the occupied regions. Prominent Kremlin propagandist Margarita Simonyan even praised Ivanishvili’s promise, commenting on Twitter that “Georgia is acting in a surprisingly rational way, as if emerging from a long-term binge or psychosis.” In general, however, Moscow appears unwilling to take further steps in this direction as long as Georgia maintains even formal ties with Euro-Atlantic structures.

Balancing Territorial Integrity and Russian Influence: What’s Behind GD’s Narrative?

The GD leadership generally sees the heated competition among great powers (US, EU, Russia, China, Iran, Turkey) in the South Caucasus as a temptation to pursue a multi-vector foreign policy until the geopolitical uncertainty is settled. This would be supported by the domestic political situation and the regime’s own tendency toward authoritarianism. The essence of GD’s policy is for the ruling elite to maintain its power for an unlimited period and minimize the government’s economic and political dependence on the West.

Furthermore, it seems that the new strategic realignment in the South Caucasus has sparked cautious optimism in Tbilisi. Russia’s apparent shift away from traditional alliances—as evidenced by Armenia’s setbacks, the collapse of Nagorno-Karabakh, and Azerbaijan’s restoration of its territorial integrity with Turkish military support and the Kremlin’s tacit approval—has raised hopes that an authoritarian “Conflict Resolution” scenario will also unfold in Georgia. Moreover, as Georgia, Turkey, and Armenia play key roles in circumventing sanctions, Tbilisi has recognized that Moscow—strained by Western sanctions and reliant on the North-South Transport Corridor to access Iran, Türkiye, India, and the Gulf states—might face constrained regional leverage, potentially creating opportunities for Georgia to reclaim territories under de facto Russian control.

In the context of the introduction in Georgia of a Russian-inspired law on “foreign agents,” this possibility has sparked concerns among Kremlin-backed local elites in Sokhumi and Tskhinvali. Their fear is that Moscow—which lost its strategic influence in the South Caucasus after the Second Karabakh War in 2020—might “return” the regions to Tbilisi to gain geopolitical leverage over the broader region and counter Western influence. According to the media, while local authorities in separatist entities have avoided publicly addressing this issue, they fear that improved Russian-Georgian relations could come to jeopardize their de facto sovereignty. As one commentator rightly put it, this scenario “would benefit Moscow, as it would permanently bind Georgia to itself with the lure of Abkhazia.”

However, while Russian officials appeared satisfied with the outcome of Georgia’s elections and the GD government’s recent foreign policy moves to distance itself from the West, it remains unlikely that the Kremlin would relinquish its leverage over Georgia without Georgia’s complete repudiation of its Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

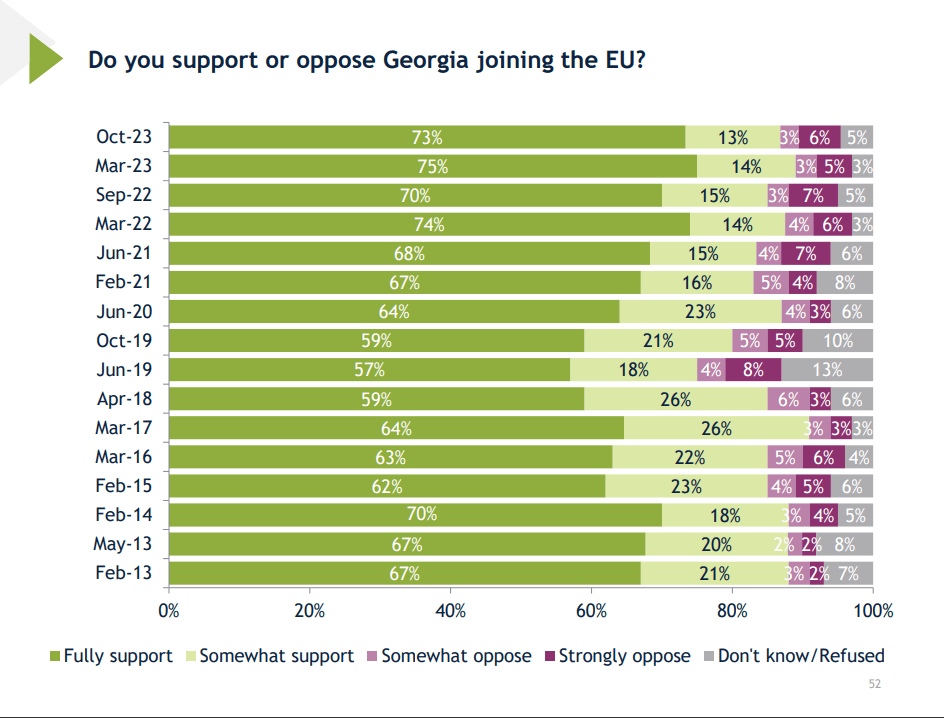

Furthermore, occasional discussions among expert communities about a potential confederation uniting Abkhazia and South Ossetia with the rest of Georgia under Russian tutelage seem implausible. First, such a hypothetical arrangement would be a major blow to Russia’s great power status internationally, as it has already recognized the sovereignty of Georgia’s breakaway regions and might therefore lose credibility among its strategic partners. Second, the arrangement appears to lack traction among the populations of the breakaway regions. While South Ossetian elites still harbor hopes of joining Russia, the recent political crisis in Abkhazia showed the Kremlin that while the occupied regions’ political and economic dependence on Russia is growing, it is no easy task to subordinate the regions’ future to Russian geopolitical interest. Third, this framework would be a difficult sell for the Georgian public, as it effectively subordinates Georgia to Russia and its breakaway regions rather than reintegrating the latter into the Georgian state, undermining the very notion of sovereignty and territorial integrity. Moreover, while Georgia in December 2023 achieved EU candidate status, this progress has effectively stalled due to concerns in Brussels over democratic backsliding. Notwithstanding this setback, an overwhelming 80% of the Georgian public continues to support European integration—a sentiment that is both undeniable and impossible to ignore.

Source: Georgian Survey of Public Opinion | September – October 2023(International Republican Institute- IRI)- https://www.iri.org/resources/georgian-survey-of-public-opinion-september-october-2023/

As recent protest following the government’s controversial decision to delay country’s bid to join the European Union confirmed, the GD government cannot explicitly announce a shift away from the EU, as strong public backing underscores the enduring appeal of European values and integration, even amid challenges in aligning its governance with EU expectations.

Nevertheless, Kremlin strategists, encouraged by the Georgian Dream government’s increasingly aligned views on foreign policy and the global order, remain hopeful that Georgia’s recent drift toward authoritarian governance could create an opening for a more explicitly pro-Russian policy and the continuation of the post-election rapprochement. On the pretext of promising to restore Georgia’s territorial integrity, Russian political elites and their allies do not exclude Georgia’s integration, in the long term, into Russia-dominated structures within the post-Soviet space and beyond, such as the CIS, the Eurasian Economic Union, or even BRICS.

As Georgian Dream officially adheres to a policy it describes as “strategic patience” toward Russia, the long-term implications of this approach remain uncertain. While the government emphasizes maintaining peace and stability as a priority, questions persist as to the extent to which it can restore diplomatic relations with the Kremlin without compromising Georgia’s security and sovereignty. Any rapprochement with Russia carries significant risks, including the potential erosion of Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations and a weakening of its ties with Western allies. Overall, as Moscow diverts its resources and focus to the ongoing war in Ukraine, the outcome of this conflict will significantly impact Georgia’s future and the broader regional security landscape in the South Caucasus.

Conclusion

Georgia’s pursuit of a multi-vector foreign policy—balancing alliances with the EU, the US, Russia, China, and regional neighbors—presents a growing strategic challenge. As Georgia deepens its strategic ties with China and Russia, these relationships risk complicating its engagement with Western partners, making the balancing act increasingly difficult to maintain. This dynamic underscores the tension between fostering economic and strategic partnerships in the East and sustaining Euro-Atlantic aspirations.

The October election results have further weakened Georgia’s resilience, as a one-party-dominated parliament lacks both internal and external legitimacy.

This instability benefits the Kremlin, as a more divided and polarized Georgian society makes it easier for Moscow to strengthen its strategic influence. It is also true that the more authoritarian, inward-looking, and internationally isolated Georgia becomes, the easier it will be for Russia to keep Georgia within its sphere of influence. If Moscow succeeds in derailing Tbilisi’s Euro-Atlantic aspirations, it could not only regain lost influence over Georgian politics, but also undermine Armenia’s rapprochement with the European Union.

As the EU requires reliable partners in the South Caucasus and access to critical trade and connectivity routes, Georgia’s lack of security guarantees from Western institutions leaves it vulnerable to Russian pressure. This vulnerability has been further exposed by Russia’s war in Ukraine, which has heightened Georgia’s security dilemma. As a result, it is likely that the Georgian Dream government will seek to deepen relations with Moscow to avoid antagonizing its northern neighbor. At the same time, GD’s attempts to strengthen ties with Russia while simultaneously reconnecting with the West risk creating a fragile diplomatic balancing act, potentially increasing Russia’s influence in Georgia at the expense of further straining its relationships with Western partners. Morever, the Russia-accomodating policies of the current regime, coupled with similar practices of strategic corruption, risk further eroding Georgia’s socio-economic resilience and stability, drawing the country deeper into Russia’s economic orbit and political influence.

[1] GD declares 2024 elections referendum on war vs. peace, traditional values vs. moral degradation. Available at: https://1tv.ge/lang/en/news/gd-declares-2024-elections-referendum-on-war-vs-peace-traditional-values-vs-moral-degradation/

VIEW FULL DOCUMENT

🔗 No. 322: Russia and the South Caucasus

Author(s): Kornley Kakachia, Nigar Gurbanli, Anar Valiyev, Narek Sukiasyan, Hannes Meissner, Johannes Leitner

Series Editor(s): Fabian Burkhardt, Robert Orttung, Jeronim Perović, Heiko Pleines, Hans-Henning Schröder

Series: Russian Analytical Digest (RAD)

Issue: 322

Publisher(s): Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich; Research Centre for East European Studies (FSO), University of Bremen; Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES), George Washington University; Center for Eastern European Studies (CEES), University of Zurich

Publication Year: 2024