Author

Frauke Seebass

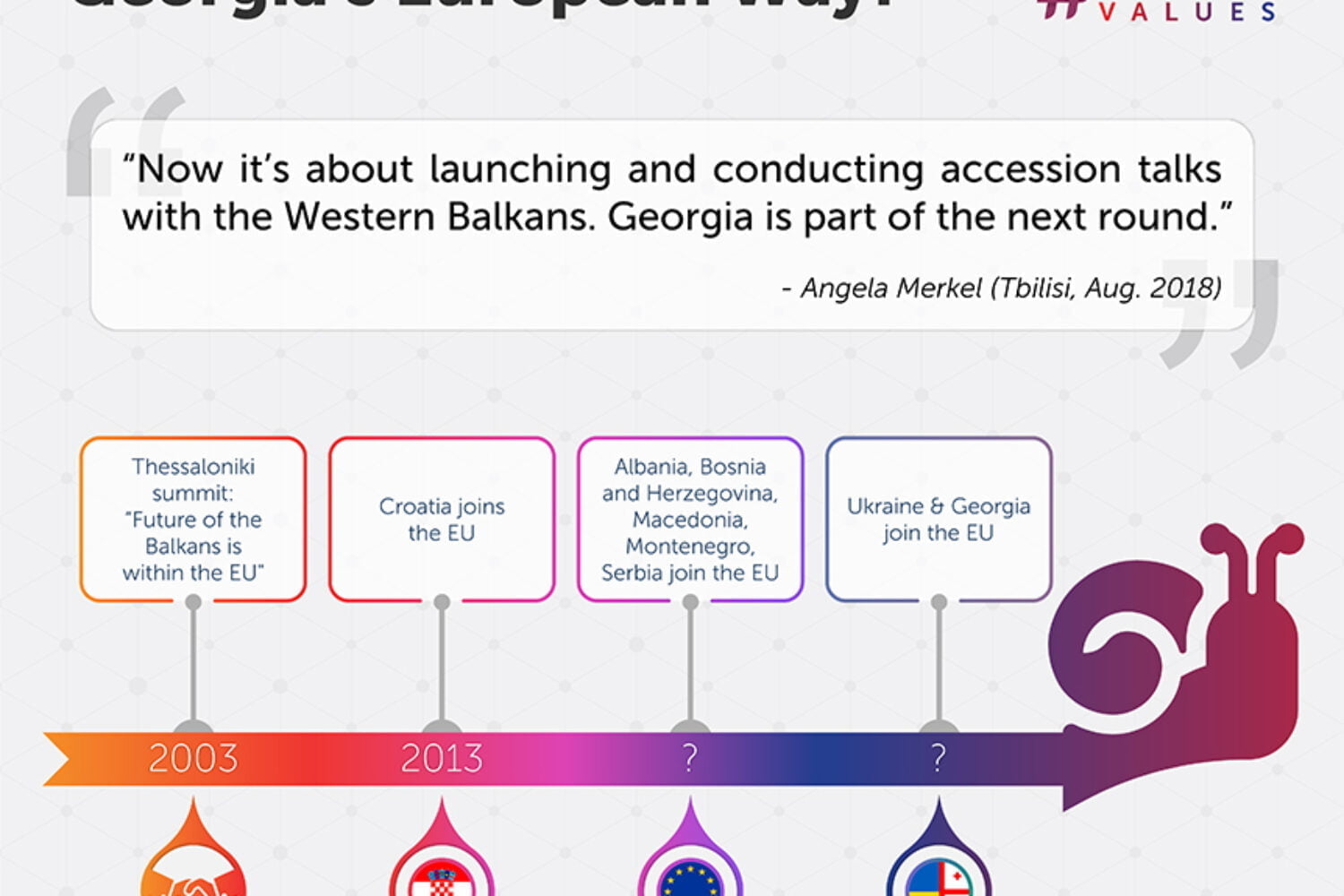

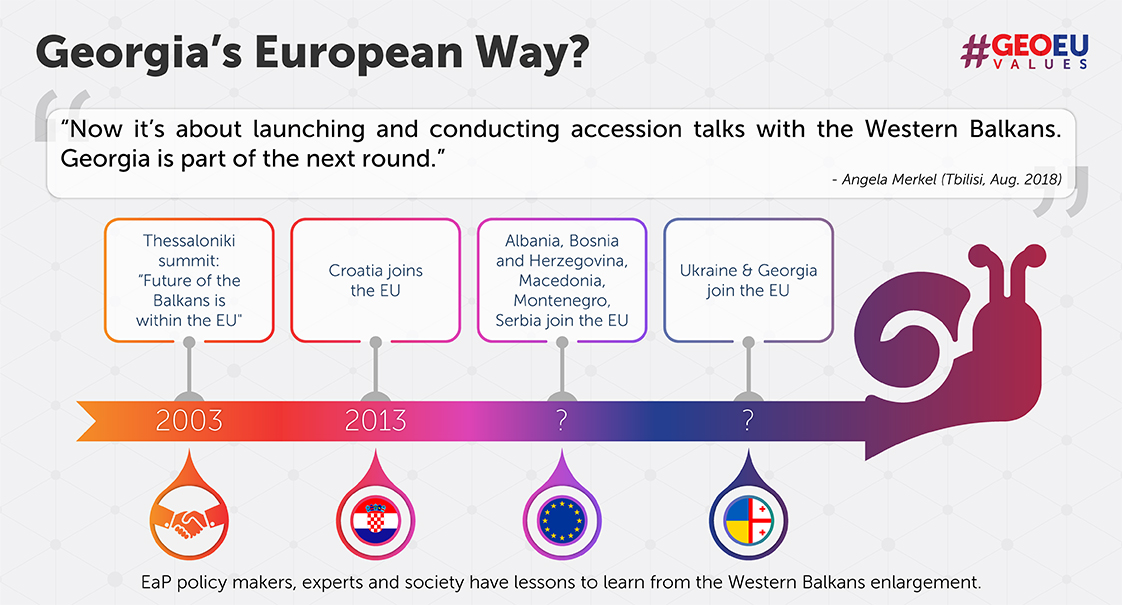

In the fifteen years since the Thessaloniki declaration confirmed the European accession partnership with the Western Balkans, only Croatia has succeeded in joining the Union. However, a new momentum has emerged this year, with the Commission seeing a new “credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans”, and the possible opening of accession talks with Albania and (Northern) Macedonia in 2019.

As for the Eastern Partnership countries (EaP), none of them has submitted a membership application yet. During her recent trip to Tbilisi, German chancellor Merkel confirmed Georgia’s EU-perspectivetogether with Ukraine and Moldova promoting closer cooperation, but at the same time dimming hopes of a fast accession track. Only after the Western Balkans, she said, they could be part of a further round of enlargement, inextricably linking the European futures of the two regions. The following six lessons from the Western Balkans can thus serve to enhance the understanding of potential EU accession processes of EaP countries.

1. Take ownership

“The future of the Balkans is within the European Union” – thus reads the Thessaloniki declaration of 2003, reconfirmed in the current strategy as being “in the Union’s very own political, security and economic interest”. Yet, there was little progress in the countries and possibly even less commitment from the EU since. As such, it seems slightly ironic to now mark 2018 as a “historic window of opportunity” for the region. At the same time, the metaphor suggests that said window might close at any moment and the opportunity lost – with consequences yet unknown. If this is true for a region of such strategic (geographical) importance for the EU, the EaP countries know how high (read: low) they are on the agenda of an inward-looking EU. Therefore, they need their own perspectives – the EU does not seem to have a plan B to accession, and its priorities are clearly elsewhere.

2. Foster regional cooperation

Bilateral economic relations between the Balkan states and the EU are flourishing, as are other forms of cooperation such as education and cultural exchange. However, with tensions high at many of the region’s borders, internal trade is minimal and the movement of people throughout former Yugoslavia has drastically diminished. Expanding regional liaisons is thus a prior demand in the new strategy as key to development and reconciliation. While their situation today is very different, a feature EaP countries share is their collective history as part of the Soviet Union, together with the many current socio-economic challenges linked to that past. Finding common positions on challenges as diverse as brain drain and relations to Russia can thus strengthen political positions including in international fora, and strategic cooperation on political and civil society levels is bound to prove beneficial in many regards, with or without eventual EU integration.

3. Communication is key

While the EU is by far Serbia’s closest partner especially when it comes to economic issues, Russia always gets the friendship ribbon despite their minor and often disruptive role – a tendency that can be observed in many Western Balkan countries. With support declining among the populations of both current and potential member states, it is extremely important to generate realistic expectations regarding EU accession and potential membership – and to explain their perspectives in the EU capitals as well. Media, civil society and citizen dialogues can help in moving issues from stuffy conference rooms to common citizens, including in rural areas. The commitments made by governments in the association process impact their lives, and sometimes painfully so. If they are excluded from the debate, they will easily lose faith in the process – and readily fall prey to anti-integration populists using popular dissatisfaction for their own interests.

4. Be prepared for a rocky road

Saying that the EU is practicing polite restraint towards the EaP countries’ accession ambitions would be an understatement. Merkel’s vague remarks after much pressure in Tbilisi have resonated throughout the country, and yet it is far from being a promise. Just to look at some of the bigger ‘ifs’ – at this point, who can tell if the Western Balkans will ever become full members? Even if the Western Balkan countries overcome all hurdles, the stakes will be much higher after their accession, as we have seen after every accession so far. Perseverance and frank communication (see #3) instead of false promises are indispensable. Setbacks are bound to be part of the way, and only a neat stack of resilience will bring you through a frosty winter towards a slightly warmer European spring.

5. All for Europe? Engage!

Are you determined to see a yet larger EU rise to its full potential? In that case, get involved! Make demands – in your country and in Brussels. It might be just your dedication that will eventually tip the scales and make that vision a reality. On a policy level: step up engagements for treaties already in place and foster cooperation with the EU in areas where integration has progressed, such as personnel in EU missions abroad. Similarly, bilateral ties with member states should be established and improved. Look at the Western Balkans’ Berlin Process: sometimes one friend is all you need to bring back the spotlight. While the process is often criticised for its lack of results, it helped in bringing the region back on the European agenda and inspired regional cooperation fora such as the Western Balkans Fund (WBF) and RYCO, the Regional Youth Cooperation Office. Together with pan-European projects such as the Erasmus+ programme or Creative Europe that have been extended to partner countries, these enable networking and participation in Europeanisation processes by individuals and civil society groups with the goal to foster regional and interregional cooperation.

6. And finally: think outside the box

This invitation is to be understood both literally and figuratively. Meeting EU association criteria as a mere box-ticking exercise is not what the process is about – even though that is easy to forget considering the bureaucratic franzy it is embedded in. After two decades of unprecedented peace and prosperity in Europe, the tables have turned and values reputedly forming the core of the Union are challenged, to say the least. Business as usual is no longer an option, but realising this seems to be a very slow process. It is time to take off normative blinkers and face reality. Poland and Hungary are not the only countries which would no longer pass the accession test today. Brexit and its consequences have still to sink in. This is not the time for doing things conventionally – internal reform is necessary, this much is clear. And maybe those outside can add a fresh breeze to revive what is left of the European spirit, if they were given the chance to contribute to a common vision and concrete steps towards it. The EU has much to learn from Ukraine’s and Georgia’s prevalent Euro-optimism.

EU integration is a process of deep transformation in the countries aspiring it, and every accession is more demanding than the one preceding it. The Western Balkan six are at different stages and it can still go both ways for all of them, presumably keeping the Eastern Partnership countries in the European waiting room for decades. It is about time we understood the association process as a means, not an end, and this is true both for the EU and the countries aspiring to join it. Overcoming internal challenges is hard, but it is bound to provide lasting benefits for the population as a whole. Fostering an inclusive debate and establishing reliable partnerships are key elements for this long and stony path. What is needed now is thus a common commitment to reform from all partners within and outside the EU’s borders to prove that its fullest potential has yet to be reached.

- Frauke Seebass – Frauke studied in Germany, Israel and the Netherlands and holds a master degree in Peace and Conflict Studies. She is employed in a project with the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP) focusing on fostering policy dialogue in the Western Balkans. At Polis 180, Frauke works on a project focusing on women in the Colombian peace process.

- The author is grateful to Dr. Pierre Mirel and Sonja Schiffers for their most helpful input to this article.

- The article is published as part of the project Between a Rock and a Hard Place? Georgian, German and French Perspectives on European Values and Euro-Atlantic Integration. The project is funded by the German Federal Foreign Office in the framework of the programme “Expanding Cooperation with Civil Society in the Eastern Partnership Countries and Russia”. #GEOEUvalues #civilsocietycooperation

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Georgian Institute of Politics or the German Federal Foreign Office.