Cover photo: Eana Korbezashvili/civil.ge

Salome Kandelaki[1]

Due to the severity of the epidemiological situation caused by Covid-19, Georgia has entered a difficult socio-economic stage. To prevent the collapse of the healthcare system, the government imposed a range of targeted restrictions, including closing shops, restaurants, and fitness centers, as well as halting public and intercity transport. As a result, the country has faced a deepening economic decline and a further worsening of the broader social situation. By November 2020, 162 220 citizens had lost their salaries due to the pandemic, and the situation for unregistered street vendors and socially vulnerable people had become acutely complicated.

The financial assistance package developed by the government is not sufficient to achieve a tangible social impact due to a number of systemic and legal reasons. In particular, an insufficiently effective tax system, outdated formulas used to calculate the subsistence living level, and the lack of an anti-crisis economic plan focused on the needs of citizens were impediments to tackling the pandemic successfully.

Does the 300-GEL package meet the challenges?

Against a backdrop of restrictions, the government introduced a targeted social assistance package which would allow people working in shopping malls, markets and retail shops – some of the earliest groups impacted by the coronavirus – to receive a one-time 300-GEL payment. The exact number of beneficiaries of this program has not been announced, but at a special briefing on November 27, Prime Minister Gakharia estimated the number would reach 100 000. He also noted that the government had already started communication with hiring companies to register their employees. This process, in a properly functioning taxation system, would have already been complete and available to the Revenue Service.

It is also unclear, what information should be submitted by self-employed people and people not registered in the Revenue Service database. During the first wave of the pandemic, unregistered self-employed people had to submit monthly income and turnover statements to their bank. Individuals who receive their income in cash, for example, babysitters or cleaners, are unable to receive assistance during the second wave without submitting a formal document. The first obvious example of social protest regarding the mentioned restrictions was civil disobedience by street vendors at the so-called Istanbul market who blocked the road on the grounds that they do not meet any category for receiving social assistance.

Even if the above-mentioned groups receive assistance, a one-time 300-GEL package is not enough, especially against the background of increased food prices and a depreciated lari. It remains obvious that no state aid can fully compensate for the profits lost during the restrictions period. However, it is important to consider whether the other family members of the 300 GEL beneficiaries are employed, how many family members there are, whether any of them have special needs, and what the total necessary monthly family expenses have been so far. Instead of an equal distribution of 300 GEL in aid, the state should tailor this aid to the needs of a specific family and, as a result, redistribute the money more efficiently.

To what extent is the government social package tailored to the needs of particularly vulnerable groups?

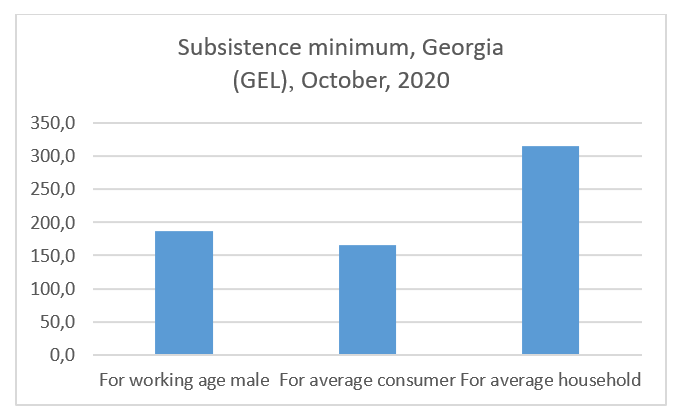

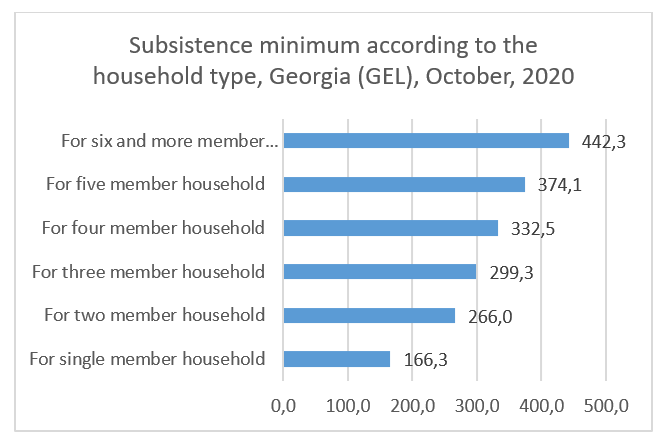

The subsistence level in the country, calculated according to legislation adopted in 1997, is clearly not in line with today’s reality. According to the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat), the subsistence minimum for working-age males in October 2020 was 187.7 GEL (Chart 1). The subsistence minimum for a single-member family is 166.7 GEL, and for six and more member households – 442.3 GEL (Chart 2).

Chart 1: Subsistence minimum, Georgia (GEL), October, 2020

Chart 2: Subsistence minimum according to the household type, Georgia (GEL), October, 2020

Source: National Statistics Office of Georgia. (10,2020), downloaded from https://www.geostat.ge/ka/modules/categories/49/saarsebo-minimumi (download date: December 3, 2020).

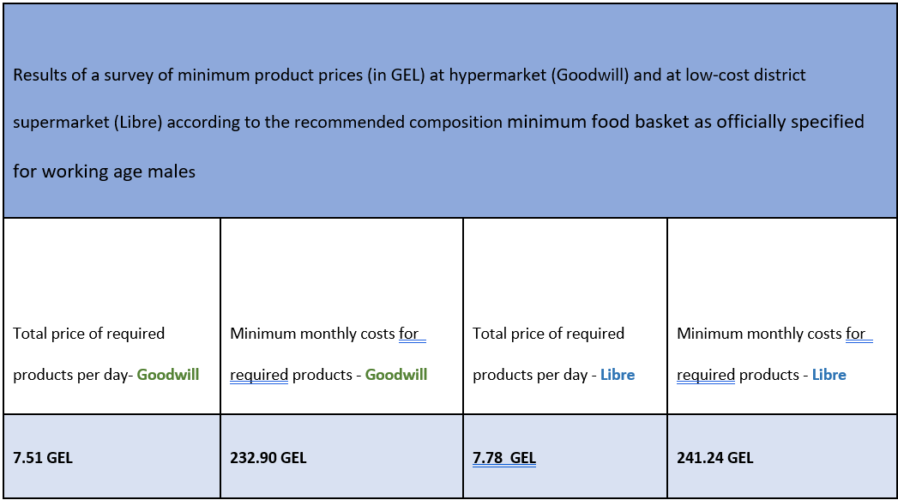

The subsistence minimum calculation does not take into account utility bills, transportation costs and many other necessary expenses. The calculation is based only on the price of food. The table below shows the results of a price survey conducted by the author at hypermarket Goodwill, and supermarket Libre, considered a low-cost district supermarket (Table 1). Based on a survey of the lowest-priced products, we can roughly calculate how much of the recommended composition of the minimum food basket, 40 types of products, it is possible to purchase at the subsistence level for a working age male in October 2020 (187.7 GEL per month, or 6.05 GEL per day). Based on the calculation, it is revealed that the daily subsistence level for a working age male needs to be at least 7.50 GEL (according to the prices of Goodwill products) or at least 7.70 GEL (according to the prices of Libre products) in order to purchase the minimum food basket set by the government.

Based on current food prices, the subsistence minimum for working-age males should be between 230 and 240 GEL per month. It should be emphasized that the main criterion for selecting products within the food basket was price, and therefore the quality or healthiness of these products was not considered and should be subjected to separate study. Additionally, while it is virtually impossible to buy the full food basket on the subsistence minimum for a working age male, the subsistence level neglects entirely other daily human requirements such as personal hygiene supplies, medicine, and clothing. It is noteworthy and counter intuitive that the prices at the low-cost, district supermarket were slightly higher than at the larger hypermarket.

Table 1: Results of price survey of Goodwill and Libre, December, 2020

Source: 1. Official webpage of Goodwill hypermarket, (05.12.2020), data obtained from https://goodwilldelivery.ge/index.html, on December 5, 2020; 2. Libre supermarket (06.12.2020), data obtained on the basis of store visit. See complete results of price survey: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1pAC7nY14dETnW4wXcp13s_GnTH2AP0TR/view?usp=sharing

Targeted social assistance for the most vulnerable members of society, like socially unprotected groups, or for people with disabilities, amounts to 100 GEL per month for 6 months, which, as already noted, is insufficient to purchase the subsistence minimum basket of food. According to the data of the National Statistics Office of Georgia as of October 2020, there were 510,343 beneficiaries (13.7% of the population) on subsistence allowance benefits. Qualification for this allowance is determined by a points system, according to which householder members receive between 30 and 60 GEL a month. A single-member household receiving social allowance and the additional 100 GEL assistance which has been allocated during the pandemic period, will still fall short of the subsistence minimum set by Geostat.

As for the total number of recipients of the social assistance package according to the different groups (e.g: between 0-18 aged person with disabilities, war participants, politically repressed people and etc.) it was 174,894 persons in October 2020. Each group receives different amounts in accordance with the Law of Georgia On Definition of Social Package. At first glance, this allowance package is relatively larger in comparison with the assistance for socially vulnerable persons, although the criteria is quite strict. For example, a parent of war dead with definite disabilities, who lost 3 children, will receive a paltry 309 GEL. It is noteworthy that a state allowance package in the amount of 62 to 77 GEL per month is allocated for various categories of people recognized as victims of political repressions. As compared to social allowance beneficiaries, the social package recipients may have other sources of income as well which may, to some extent, alleviate their social conditions.

Stopping municipal transport was especially problematic for people with disabilities (PWDs) and socially vulnerable people with chronic diseases. These socially vulnerable groups, some of which require continual treatment, are not provided with transportation. The lack of transportation options and assistance during such restrictions is tantamount to neglecting the health issues of people with disabilities. Before announcing movement restrictions, it is necessary to determine the risks caused by these restrictions and to take into account the logistical details essential for the health of the population, particularly the socially vulnerable.

During the second wave of the coronavirus, decisions the government made to avoid overloading the healthcare system did not adequately correspond to the challenges faced by the already impoverished segments of the population. Given that the first wave of the virus was stopped relatively successfully, the government could have better prepared for the inevitable second wave. For example, it was possible to take preliminary economic measures before the announcement of restrictions and to study the socio-economic state of the families of registered employees. This would have allowed the government to determine a social package based on the specific needs of actual households.

Another change that could have been considered is a reformulation of the subsistence minimum, the calculation of which, as mentioned above, is regulated by legislation which does not conform to today’s economic reality. Consequently, we end up with a chain of problems, the solution of which requires fundamental systemic and legislative changes that cannot be solved quickly. One mitigating factor of the difficult socio-economic situation may have been the restructuring of bank loans and the provision of assistance to bank-dependent entrepreneurs and street vendors more or less proportional to their activity. The substantial financial aid received by the Georgian Government could have been distributed more effectively and caused greater positive impact. With the money spent attempting to counteract the socio-economic effects of the second lockdown, they could have increased the capacity of private hospitals, and the number of medical workers while creating financial incentives to minimize lethality and economic losses.

[1] Junior Policy Analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP)