Author

Nikoloz Tokhvadze

10 years ago, when the Polish-Swedish tandem initiated the Eastern Partnership (EaP), the expectations in the region were overly hopeful. Having leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan posing together on the podium and president Lukashenko on the guest list,[2] spelled brighter future on the EU’s freshly expended eastern frontiers.

Georgia, still recovering from the 2008 war with Russia, was also represented on the summit. Country’s leader at that time – President Saakashvili – assessed the historic moment as “a step closer to a family” and ruled out turning back from the chosen path.[3]

The chosen path itself was aptly encapsulated in the initiative’s founding declaration in Prague, in 2009. The document worded out the objectives of the partnership to be based on „fundamental values, including democracy, the Rule of Law and the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms… “[4]

The timing of the launch was also significant as it inadvertently coincided with the Freedom House’s account alerting the world about the eroding democratic zeal in most of the regions[5] and prophesizing “the Great Democracy Meltdown.”[6] From this perspective, having a concept of “Democracy” firmly anchored in Georgia’s Eastern Partnership agenda meant to mitigate the adverse trend.

A decade later, as the policy matured, it is imperative to ask whether the Eastern Partnership managed to fulfill its pledge of advancing Georgia on the strenuous road of democratic transformation. Curiously, the 10th anniversary of the Eastern partnership again coincides with tectonic democratic changes in the world, this time – the end of the decade-old democratic retreat.[7] It there also a modest Georgian contribution in this reversed trend?

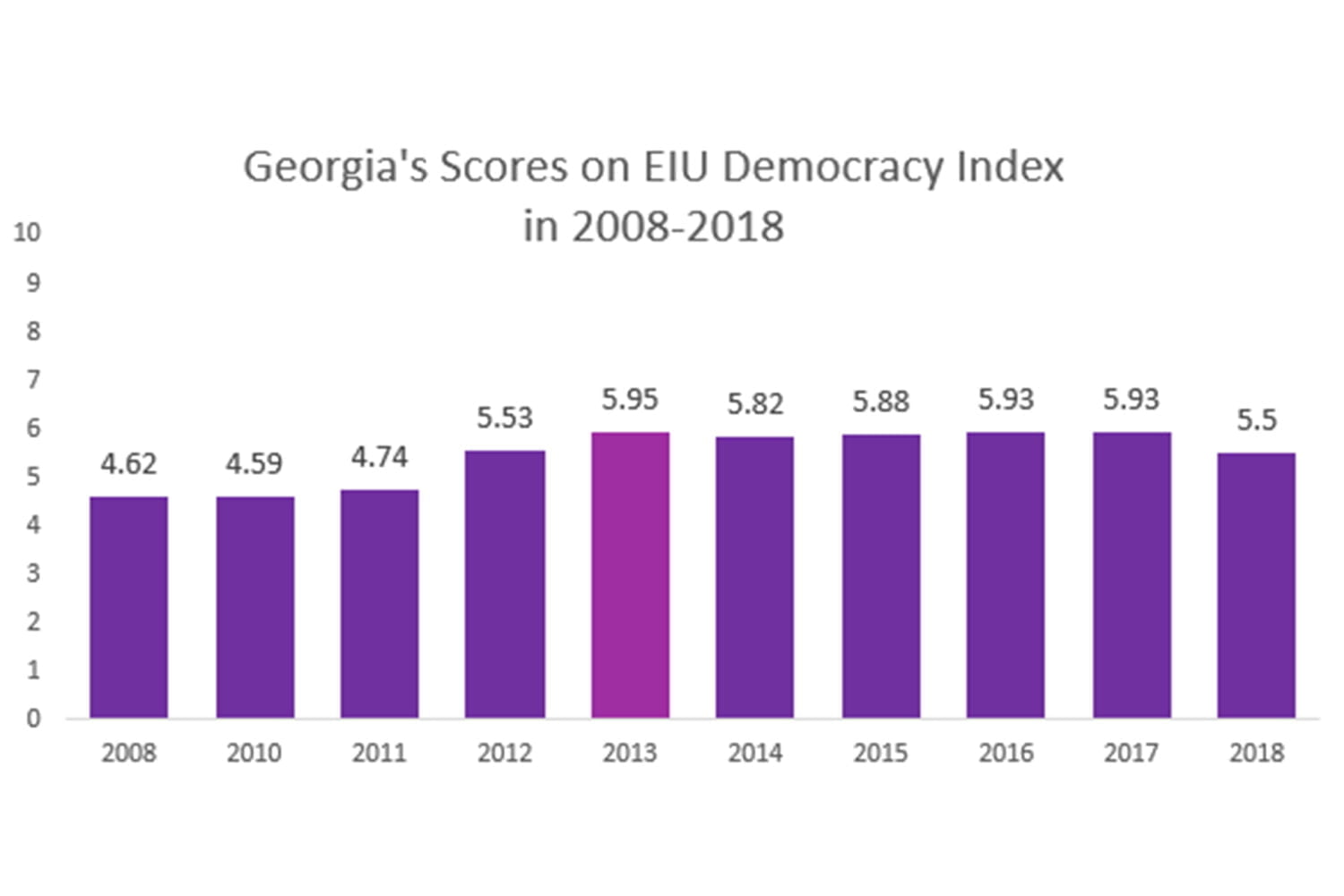

During the last 10 years, the democratic performance of Georgia has varied only slightly, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. In almost a decade, Georgia managed to improve its score from 4,62 to only 5,5 on a 10-point-scale. For reference, with this pace, it would take Georgia another 40-50 years to catch up with the current leader of the democracy board – Norway.[8] This too, assuming a constant upwards trend which not always is the case. During the last decade, Georgia remained in the “hybrid regime” category once again hinting on the relatively low overall change in the country’s democratic transformation. While the overall democratic gain is insignificant, the year 2012 and particularly the 2013 stand out due to relatively high gains.

| [9] Scale 1-10 / higher score = more democratic |

The underwhelming democratic performance is at odds with the Eastern Partnership’s declared objectives and the enticing rewards. Can the fluctuations in Georgia’s democratic score, particularly in 2012-13, be traced to the EaP’s main milestones? How are the Association Agreement and the Visa Liberalization mapped on the country’s timeline?

To ensure the uninterrupted progression on the democratization agenda in Georgia, the EU utilized one of her most successful tools – the democratic conditionality. The rationalist logic of conditionality assumes that actors can be motivated into action by offering them corresponding rewards.[10] The pattern of the EU’s conditional efforts in Georgia can be broken down into two: 1. the annual actions such as advancing the strategic objectives of the EU-Georgia Action Plan[11] and 2. perusing more enhanced cooperation through embedding individual one-time rewards in the roadmap. Two major rewards – an extensive Association Agreement (also encompassing a free trade agreement) and a Visa Liberalization were thought to have a strong enough gravitation to accelerate the pro-democratic reforms.[12] While the first type of effort yields more consistent results due to the predictable nature of the 5-year-long Action Plan’s annual cooperation scheme and financing, the latter was thought to deliver more irregular yet powerful transition incentives.

Despite the continued nominal adherence to the objectives of the Action Plan by the Georgian government, the state of democracy during the first several years of the EaP remained largely turbulent. This is mostly to be attributed to President Saakashvili’s tightening grip on the government. The detention conditions and torture of prisoners, low media freedom, and limited right of the assembly were frequently criticized by the EU Commission.[13] Other non-democratic practices such as the lacking consolidation in areas of justice and human rights, and the government’s potential political interference in the judiciary were also seen as crucial challenges.[14]

To remedy these problems, the EU’s Neighbourhood policy declared the reforms in law and governance as the main priority, followed by the support for economic development and eradication of poverty.[15] The declarations were accompanied by corresponding financial assistance.[16]

However, the democratic gains until the 2012 Parliamentary Elections remained negligible. In the election, Saakashvili’s power was successfully challenged by a political novice and at that time an enigmatic billionaire – Bidzina Ivanishvili.

In 2012 and 2013, Georgia made the highest democracy gains observed since the launch of the Eastern Partnership.[17] This sudden boost is to be mostly attributed to the change of the government and is not directly traceable to the efforts of the EaP. Nevertheless, the new government’s eagerness to capitalize on the Association Agreement and Visa liberalization processes facilitated the adoption of the anti-discrimination legislation aimed at protecting minorities. This further contributed to pro-democratic processes.

2013 also became determining for Georgian democracy due to Ivanishvili’s decision to retreat from active politics and relinquish the post of a Prime Minister to a queue of his teammates. This spelled a start of a dangerous spiral of Ivanishvili’s “informal Government”, lack of accountability, and the end of significant pro-democratic processes which dragged through the end of the Eastern Partnership’s first decade. [18]

Upcoming Association Agreement in 2014-2015, created a potent facet for pushing democratization reforms and consolidating Georgia’s institutions. For instance, the country’s commitment to the public administration reform in order to fight corruption or adoption of the Equality and Integration Strategy to fight discrimination, are good examples of the EaP-engendered democratic transformation. Nevertheless, behind the façade changes a practical implementation of the new regulations were hampered by the lack of effective sanctions and preventive measures.[19]

Furthermore, despite the proclaimed momentous importance of the Agreement which was thought to be a reward for adherence to democratic principles, neither its signing in 2014 nor its full enforcement in 2016 seems to have significantly affected Georgia’s democracy scores. The marginal democratization trend observed in previous years was further carried out without irregular changes.

It is also notable that while democratic conditionality continued to accompany the EaP during the first decade, the minor iterations of the Partnership by the EU Commission,[20] followed by the sizable 2015 reform of the neighborhood, significantly altered the face value of the EaP’s priorities. The democracy promotion as a guiding principle was curtailed by more pragmatic notions of “flexibility” and “stabilization”.[21] This reform coincides with the start of Georgia’s “democratic staleness”.

In the following years, Georgia’s media pluralism gradually gave way to media polarization. The justice system suffered too as the government was criticized for exerting pressure on the Constitutional Court. Executing the adopted laws also remained a challenge as severe incidents such as assaulting LGBTI persons and abducting a foreign journalist were recorded.[22]

Ivanishvili’s unchecked informal governance and frequent unexpected reshuffles in the Georgian government, in the aftermath of handing out all rewards by the EU, signaled the democratization fatigue among the leading Georgian elites. This was also reflected in a significant democratic retreat for the first time since the EaP launch.

The modest democratic gains of Georgia are to be attributed to internal processes in 2012-2013. Although the EU’s two major rewards and an annual “more for more” approach did provoke significant pro-democratic reforms, they do not seem to have improved the country’s democracy at a considerable margin. This demonstrates facade compliance by the Georgian authorities while the implementation of the pushed reforms remained largely problematic.

Lastly, the EU’s 2015 reform of the neighborhood and downplaying the democratic conditionality might have sent a precarious signal to the Georgian authorities. The challenges such as informal governance, lack of accountability in the government and the lack of resolve to effectively implement the adopted laws have been dominating the Georgian political landscape in the later phase of the EaP.

After exhausting the explicit rewards, to avoid further democratic backsliding in Georgia, the EU needs to push democratic principles more assertively, come up with further external incentives needed for tangible conditionality, and, most importantly, put a stronger emphasis on implementation of the adopted norms.

[1] Nikoloz Tokhvadze – Doctoral candidate at Freie Universität Berlin

*The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Georgian Institute of Politics.

[2] Lukashenko eventually declined the invitation due to the pledged cold shoulder from Czech President – Václav Klaus. Spiegel Online (2009). Europe’s New Eastern Friend. www.spiegel.de/international/europe/the-belarusian-gambler-europe-s-new-eastern-friend-a-623269.html

[3] BBC, the (2009). EU launches ‘Eastern Partnership’ http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/8040037.stm

[4] Council of the European Union (2009). Joint Declaration of the Prague Eastern Partnership Summit, Brussels, 7 May 2009 8435/09 (Presse 78)

[5] Freedom in the World 2008. (2014, November 13). Retrieved from https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2008

[6] Kurlantzick, J. (2011, May 19). The Great Democracy Meltdown. Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/88632/failing-democracy-venezuela-arab-spring

[7] The Economist (2019). The retreat of global democracy stopped in 2018 https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/01/08/the-retreat-of-global-democracy-stopped-in-2018

[8] 9.87 points in 2018.

[9] Data for 2009 is missing due to the biennial nature of index prior to 2010.

The Economist. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. https://infographics.economist.com/2019/DemocracyIndex/

[10] Schimmelfennig, F., & Sedelmeier, U. (2004). Governance by conditionality: EU rule transfer to the candidate countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of European Public Policy, 11(4), 661-679. doi:10.1080/1350176042000248089

[11] Action Plans are political documents signed by the EU and a partner country usually for a 5-year term (term can vary). To ensure a smooth implementation of the Action Plan’s mutually agreed objectives, the EU provides financial incentives and support for the reforms (stemming from the objectives) and annually monitors and benchmarks the results.

[12] Boonstra, J., & Shapovalova, N. (2010). The EU’s Eastern Partnership: one year backwards.

[13] European Commission (2010). Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2009: Progress Report Georgia

[14] Transparency International (2011). The annual Report 2010. https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/transparency_international_annual_report_2010

[15] European Commission (2010). C(2010) 3330 final. Annual Action Programme 2010 in favour of Georgia https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/enpi_2010_c2010_3330_annual_action_programme_for_georgia.pdf

[16] European Commission (2011). C(2011) 4966 final. Annual Action Programme 2010 in favour of Georgia Brussels https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/enpi_2011_c2011_4966_annual_action_programme_for_georgia.pdf

[17] Freedom House (2013). Georgia report 2013.

[18] Agenda.ge (2016). Ex-PM Ivanishvili on election results, ‘informal governance’ and competitors of GD http://agenda.ge/en/news/2016/2050

[19] European Commission (2016). Association Implementation Report on Georgia http://www.3dcftas.eu/system/tdf/1_en_jswd_georgia_0.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=267&force=

[20] Korosteleva, E. (2017). Eastern Partnership: bringing “the political” back in.

[21] Lannon, E. (2015). More for more or less for less: From the rhetoric to the implementation of European Neighbourhood Instrument in the Context of the 2015 ENP review. IEMed Overview”, European Institute of the Mediterranean, Barcelona.

[22] European Commission (2017). Association Implementation Report on Georgia https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/association_implementation_report_on_georgia.pdf

Nikoloz Tokhvadze