Author

Clara Weller

As the Covid-19 crisis was reaching Europe, the EU struggled to take a common decision on its territory. Today, the Union learns from local-level solutions. Member states’ cooperation and regional organization display the high potential of deepening regionalization. When the sanitary crisis adds to the background of rising euroscepticism towards Brussels, the regionalized response endorses a relevant political meaning. Rethinking crisis management by a bottom-up approach should bring an efficient resilience for the EU.

How challenging is the crisis for the EU response

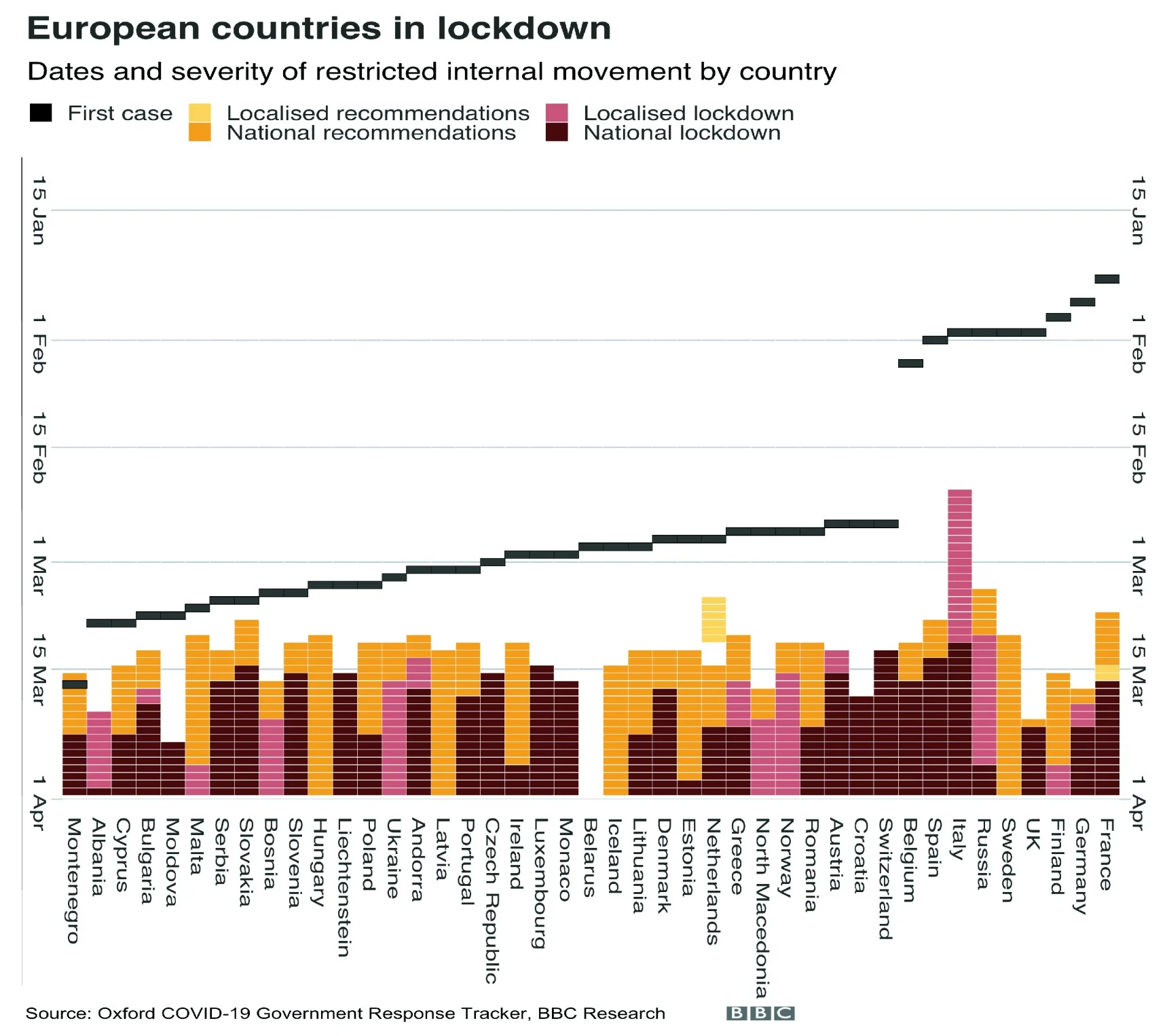

Member states withdrew into themselves since the beginning of the crisis, applying different lockdown policies in most cases independently from EU structures. The lack of anticipatory harmonized measures has been evident. Even if the EU does not have health prerogatives – which belong to State domain only – the start of the European institutionalized cooperation came late. The first official EU statement regarding the virus arrival in Europe is dated from the end of February whereas the spread started a month earlier. This underlines how much the threat was underestimated at the time. Even if Italy was the first European country to establish nationwide state of emergency with 8,000 active cases on March 9th, member states’ reactions came even later after the outbreak, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: European countries in lockdown

After weeks of efforts, European countries are eventually organizing the end of the quarantine, which in turn brings in economic management issues. The problems related to harmonization are extending even further vis-à-vis the forthcoming financial plans. There is a clear split between member states due to the concerns about the debt: whether to create corona-bonds or not. Shared debt instrument has always been a delicate topic, especially today as some countries are calling for a mutual European debt. Germany and Netherlands oppose it, raising Italian apprehensions about its future. The opponents fear that they will have to pay for the southern European countries, which are more affected economically than others.

The EU has difficulties to plan a global response on multiple scales. European unity and solidarity have been highly challenged by the crisis both economically and politically. However, the response may be found in a more local approach.

A call for a more regional crisis management

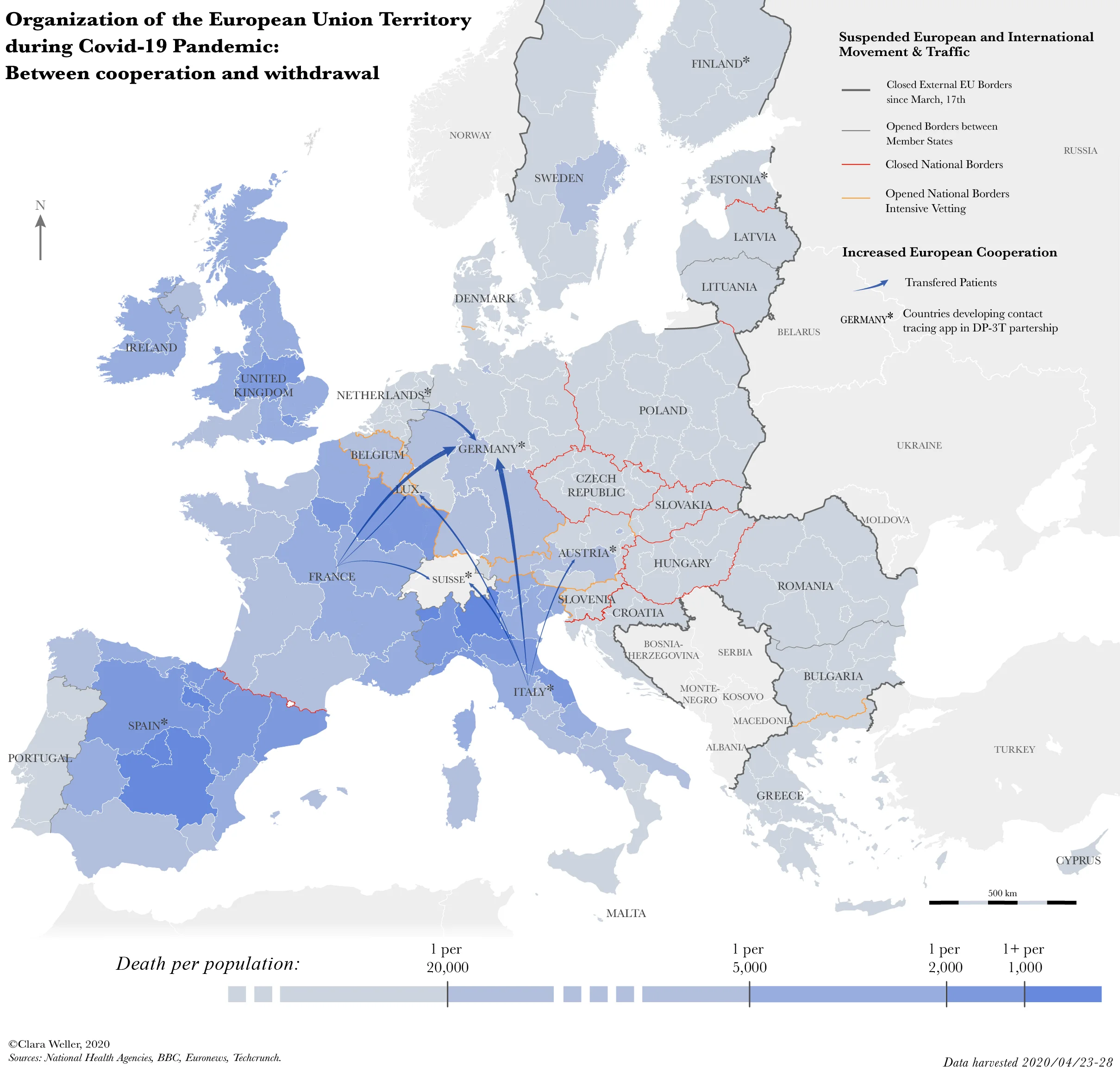

A global response is expected from the EU, but there is a clear geographical disparity among member states and within their regions (see the map below). It could be more relevant to consider local answers at a country level than a global one. There is a large gap between the most affected areas, in the North of Italy (Lombardy and Veneto), in the South-west of Germany (Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg) or in France (Grand-Est), and the less affected ones as the South of Italy. Different types of challenges with regard to health-care systems require targeted, region and country-specific solutions.

For some reason, Germany handled the crisis better than other European countries, probably thanks to its federal shape. It gave more flexibility for decision-making and allow Landers to react quickly, as they can conduct autonomous health policies. Although other factors must be taken into account, such as massive testing, suitable and numerous equipment. These additional means and their regional deployment permit to treat cross-border patients, as shown below.

The EU is currently elaborating feedback documentations on local and regional responses to Covid-19 to be shared with all European regions. From a short- and medium-term views, it is particularly valuable to swiftly adapt sanitary measures and then strengthen regional cooperation on scientific, medical and sanitary fields. Knowledge from the resilience of local initiatives helps to mitigate the crisis by creating adapted answers to each case. One can perhaps wonder about its very next usefulness in the case of a second wave. Thus, the EU should rethink the cooperation to establish a local crisis management from bottom-up perspective.

Reinforce decentralized unity: the off balance of European critics

For several years now, euroscepticism has risen strongly, questioning Union’s role as a whole. One of the most recurring reproaches concerns the overcentralized system. The application of deeper regional cooperation could remedy the missteps in the distribution of EU powers emphasized during the COVID crisis. The bottom-up approach, by putting back the citizen in the center of the action, could be a proper reaction to populism and far right movements polarizing the public opinion. Indeed, bringing out the importance of the local level would reduce the distance between institutional powers and territorial reality.

The angle of the regional management also extends to the issue of contact tracking technologies. Tracking tools experienced in some European countries should be strictly supervised and temporary because they restrict EU fundamental rights. Due to the sanitary crisis, they are admittedly on the edge of posing a risk to privacy and civil liberties. On the other hand, it questions their further use in weakened European democracies. As a matter of fact, Vikor Orban in Hungary used the sanitary crisis to seize all executive powers for an indefinite period of time. Contact tracking apps, recognized as being of public utility to prevent from the disease, have led member states to question the consequences of their widespread use. A decentralized system called Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracking (DP-PPT) quickly outdistanced the previous Pan-European centralized one. The local processing of contact tracing presents fewer risk because it is designed to resist re-use at the individual level by a State and for time-limited use including dismantling after the crisis has passed. This is why it raised some member states’ interest but finding common agreement points, especially in a crisis context, remains a European challenge.

Clara Weller – Clara Weller is an intern at GIP and a Master student at the University Vincennes Saint-Denis, Paris, France.