Author

Joseph Larsen

Joseph Larsen and Bidzina Lebanidze

GIP Analysts

Single party rule is returning to Georgia. The ruling Georgian Dream party won 48 of 50 runoff elections for majoritarian electoral districts on October 30. Add that to the 67 seats it won during the first round of voting on October 8—Georgia’s mixed parliamentary system allocates 77 seats according to a proportional system and 73 seats according to first-past-the-post—and it will occupy 115 of 150 seats in the new parliament.

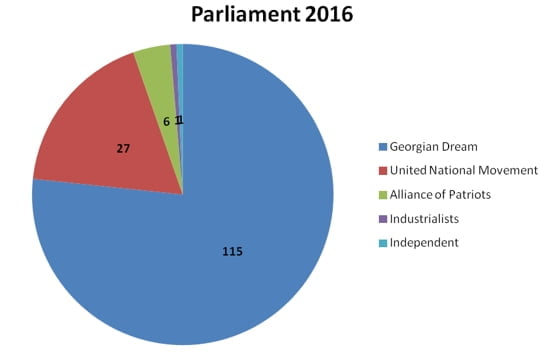

That’s significantly larger than the 85 seats Georgian Dream won while pooling efforts with several coalition partners in 2012. Now it will be free to rule without coalition support. Plus, it will have a constitutional majority: having passed the 113-seat threshold, its parliamentarians will have the power to amend the constitution without consent from any other parties in parliament. The new parliament will break down as follows: Georgian Dream will have 115 seats, followed by the United National Movement with 27, the Alliance of Patriots with six, the Industrialists with one, and the last seat going to pro-Georgian Dream independent Salome Zourabichvili.

Source: Central Election Commission of Georgia

The voting process was relatively calm, with international observers such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, NATO, and the Council of Europe assessing it positively. There were shortcomings, though. The head of the European Parliament Delegation in Georgia referenced a “high number of alleged cases of pressure and reprisals on voters, including threats of job dismissals and social benefits cuts as a result of their support for opposition candidates.” These allegations are troubling but haven’t been confirmed. Former First Lady Sandra Roelofs, a parliamentary candidate for the United National Movement in Zugdidi, refused to participate in the runoff election because she believed she received a majority of votes in the first round but lost because of manipulation. Party leader Giga Bokeria also accused the election authorities of stuffing ballot boxes to ensure a victory for Georgian Dream.

The incumbents’ near-sweep of the runoffs and the prospect of a constitutional majority are alarming to some. The party has spoken of making the office of the president elected by parliament rather than by popular vote; a move that would strengthen Georgian Dream but erode the checks and balances that underpin any well-functioning democracy. Current President Giorgi Margvelashvili has often been a thorn in Georgian Dream’s side. From a democratic standpoint, that’s a good thing. The prime minister has also expressed his priority to amend the constitution to define marriage as between one man and one woman, something which is already written into the country’s civil code. Such an amendment would hurt Georgia’s image in the eyes of its European partners while accomplishing nothing of tangible value.

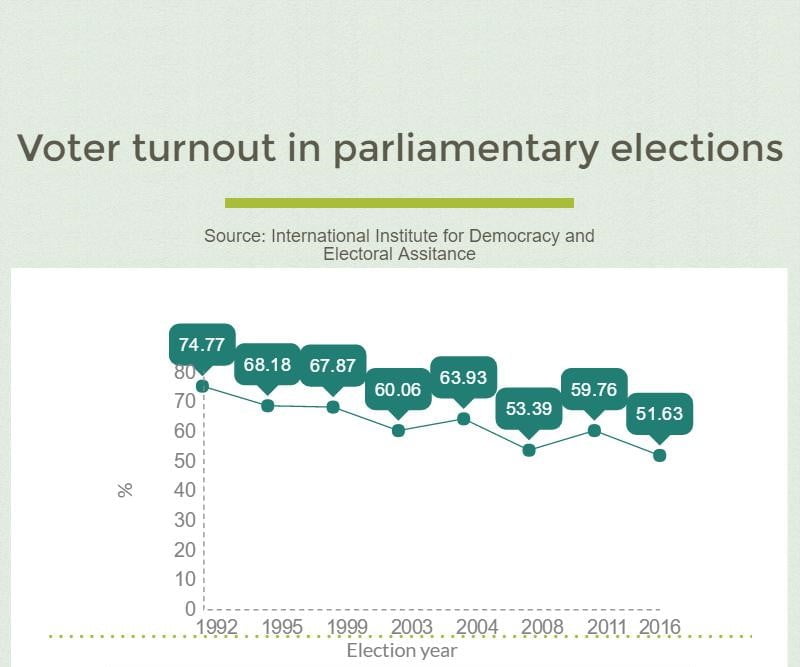

Low turnout is another concern. Roughly 51.63 percent of eligible voters went to the polls on October 8, and only 37.5 percent did on October 30. That gives 2016 the lowest turnout of any parliamentary election in the country’s short democratic history, significantly lower than the 60 percent turnout in 2012. Here’s the paradox: Georgian Dream received fewer than half of total votes cast and, when turnout is factored in, was supported by only 25 percent of the electorate. It will nonetheless be significantly more powerful than it was after the 2012 elections, when it received many more votes.

Source: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

The opposition parties share responsibility for the low turnout. The main opposition party – the United National Movement – failed to rebrand itself despite it being clear the party’s old faces and arrogant tone were reminiscent of their heavy-handed rule from 2004 to 2012. The former ruling party still hasn’t distanced itself from ex-president and party leader Mikhail Saakashvili, who spoiled the campaign by making controversial statements just ahead of Election Day.

The folly of Georgia’s pro-Western liberal parties, namely the Free Democrats and the Republicans, also contributed to Georgian Dream’s constitutional majority. It was clear before the elections that these parties wouldn’t pass the five percent threshold working alone. Yet they refused to build a coalition that could have gotten them into government. Following the election result, several members of the Free Democrats quit the party and declared the intention to cooperate with Georgian Dream—perhaps with the ulterior motive of ingratiating themselves with the new government. Similarly, former Parliament Speaker David Usupashvili quit the Republican Party to launch a solo political career.

Still, the elections were free and fair and Georgia appears to have made the move from a country in transition to a consolidating democracy. Ensuring that consolidation continues will depend on several factors. The first is Georgian Dream ruling effectively and responsibly. They must avoid the temptation to abuse their constitutional majority. Good starting points would be to strengthen constitutional checks and balances and increasing channels for dialogue with other parties, civil society organizations, and the public at large.

Transitioning from a mixed parliamentary system with a high electoral threshold—it currently stands at five percent—to a proportional system with a lower threshold would potentially increase the number of parties represented in parliament. This is particularly relevant now; the Free Democrats and the Republicans were shut out of the new parliament for failing to pass the threshold. Another welcome move would be for billionaire Georgian Dream patron Bidzina Ivanishvili to stop influencing things from the shadows; either he should enter politics on an official basis or withdraw altogether. Currently he enjoys an unhealthy combination of too much influence and too little official responsibility.

For its part, the National Movement needs to reconsider its role in society. Its days as a ruling force are over; former leaders like Saakashvili have become more hindrance than help with their unruly, attention-seeking behavior. In order to contribute to Georgia’s democratic development, the party needs to become part of a constructive opposition and present ideas for improving quality of government. Although there are sound differences in their socio-economic platforms, Georgian Dream and the United National Movement don’t occupy opposite ideological poles—both are devoted to market-oriented economic development and eventual EU and NATO membership. Working together should be easier for two groups that want essentially the same things.

Lastly, the country’s established parties need to respond to the growing popularity of nationalism. The conservative nationalist Alliance of Patriots crossed the five percent threshold to enter parliament. Its six seats won’t be enough to affect legislation but do provide a platform for propagating anti-liberal, NATO- and Euro-skeptic messages to a much larger audience. Exposure to the policymaking process may push the party toward pragmatism, but it could also use the bully pulpit to promote xenophobia. Either way, growing nationalism is something the mainstream parties can’t afford to ignore.