© Originally published: PONARS EURASIA

Georgia, once hyped as a “beacon of democracy” in New Eastern Europe, has recently become the sick man of the region. The country has become caught in a spiraling process of radicalization and polarization between the ruling party, Georgian Dream (GD), and the main opposition party, the United National Movement (UNM), as well as its splinter groups. While GD has been in regime-survival mode, deliberately slowing down the reforms required for EU candidate status, the opposition parties have also been driven by narrow party interests and have become detached from a large segment of the population. The political crisis peaked in March 2023, when GD attempted to adopt a Russian-style “foreign agent” law that would have weakened Georgia’s civil society and diverted the country from the path of EU integration.

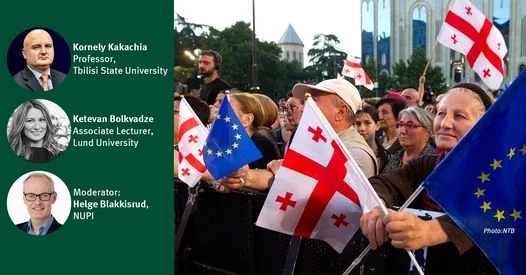

However, events took an unexpected turn. After the bill passed its first hearing in parliament, a crowd of protesters hit the streets, demanding that the bill be withdrawn. Unlike previous protests, these demonstrations were led by the so-called Gen Z, which sidelined the institutional opposition and forced the government to retract the bill.

This memo is based on focus groups conducted with representatives of Georgia’s Gen Z shortly after the March 2023 protests. The data indicate that, compared to older generations, members of Gen Z display more radical pro-European and anti-Russian attitudes. They are driven not by affiliations with any political figures, but by the values they have developed at universities. Moreover, their digital literacy and multilingualism make them largely immune to disinformation and manipulation attempts by political actors. While Gen Z alone cannot resolve all the issues facing Georgia’s struggling democracy, its entrance onto the protest scene has strengthened Georgia’s vibrant civil society—and the generation can act as a guardian of the nation’s democratic and European future.

Young, Digital, Apolitical: How Gen Z Immunized Itself from the Propaganda Toolkit

Anti-government protests are nothing new in Georgia, and incumbent regimes have managed to survive large-scale demonstrations on several occasions. However, the March protests against the “foreign agent” bill marked the first time that Gen Z entered the political scene and took charge on the streets. The demonstrations were decentralized, lacked clear leadership, and featured various performative acts. Furthermore, the protesters kept opposition parties at arm’s length and did not allow them to dominate the protest agenda.

State authorities attempted to disperse the protests using water cannons and tear gas but encountered strong resistance. Crucially, much of the Georgian public is already traumatized by violent crackdowns on protests, both by the current government and especially by previous administrations. As a result, the public is highly sensitive to state authorities’ response to street protests. Being aware of this, the GD party was cautious not to use excessive force against the demonstrators. The party was further constrained by the general youth of the defiant protesters, as cracking down on young protesters would have triggered a greater outcry among the population. Ultimately, therefore, the government was forced to retract the “foreign agent” bill. It would be no exaggeration to argue that Gen Z’s entrance onto the protest scene has significantly bolstered the resilience of Georgia’s already vibrant civil society, turning it into a force to be reckoned with.

Interviews and focus groups with leading Gen Z protest figures paint an intriguing self-portrait of this new generation (see the Appendix for more information about the Focus Groups and interview participants). Gen Z is a notably diverse demographic segment, including all those born between 1996 and 2012: the youngest members of this generation are in middle school, while older members are in university and the workforce. Compared to previous generations, they see themselves as less radical, more self-organized, and free from any obligation to obey the political authorities. Additionally, their digital literacy and multilingualism make them largely immune to disinformation and manipulation attempts by political actors. This self-image is not only realistic, but also aligns closely with the dynamics observed during the March 2023 events.

Memes Instead of Radicalization

Our focus groups first revealed that Gen Z seems to be more critical of the radicalized nature of Georgian politics and protest, which have come to focus on narrow political agendas and are driven by a zero-sum mentality. Instead, this generation prioritizes informal, peaceful, non-aggressive, decentralized, and creative protest and deliberation mechanisms, such as the spontaneously created student platform “No to the Russian Law,” which was the organized form of resistance and a platform for issue-based brainstorming by interested parties during the March protests.

In this regard, one facet of the March protests is particularly striking. Images of two women became powerful symbols of the anti-Russian Law protests. The first was of a 45-year-old woman who faced down the water cannons while holding a European Union flag. The second was of a 14-year-old girl who jumped over the water flow while holding a Georgian flag. Later, the first woman said in an interview that when she compared the two episodes, she felt that she had more post-Soviet anger in her eyes as she furiously waved her flag, whereas the girl jumped freely over the water cannons. This contrast could be a metaphor for the different generations’ approaches to the concept of protest.

Another feature of the Gen Z protests in Georgia is a mix of creativity and humor. Banners, memes, and messages were based on easily understandable and catchy jokes. Youth transferred the main messages and mood of the protest in a human, crisp, non-aggressive, and easily intelligible manner. In this way, Georgia’s Gen Z became an authentic part of a global form of protest: the Meme Movement. In interviews, representatives of Gen Z characterized this approach as more efficient and less likely to damage the eventual goal of the protest.

No Political Icons

Another important phenomenon about Gen Z that was observed during the March events was skepticism toward political authority. Unlike the older generations, Gen Z is free of personalized political icons. Instead of focusing on political or public personalities, Gen Z activists are driven mostly by the values they have developed at universities in conversation with professors and peers.

Members of the “No to the Russian Law” movement turned this fact to their advantage: They created a form of activism that was free of any affiliation with or attachment to any political power, be it in government or in opposition. This was a carefully considered move to avoid damaging the public image of the protest movement. Young protesters portrayed themselves as free of stigmas from the political past, enabling them to enjoy broad public trust and positive attention.

In interviews, members of Gen Z unanimously underlined the importance of values—instead of authorities—as the key drivers of their protest. Speaking about their mission, participants in the Focus Groups mentioned the “fight for freedom” and “keeping the free environment.” They also showed a romantic spirit (reflected in their choice of the Tbilisi State University’s Garden, a romantic place, as the venue for launching the protest movement). Affiliating their fight with the universities seems to be equally important for students of large state and small private universities alike. Overall, detaching themselves from the agendas of mediocre opposition parties and ignoring charismatic political leaders proved to be an effective strategy, making the Gen Z protests more resilient and also a difficult target for governmental propaganda.

Digital Natives

Last but not least, a higher degree of digital literacy also proved to be an important factor behind the success of the Gen Z protests. Gen Z are overwhelmingly digital natives. Many of them speak multiple languages; have access to multiple information sources; and rely on social media platforms and other digital tools for information exchange, deliberation, coordination, and organization of protests and other social activities. This makes Gen Z a difficult target for governmental manipulation, propaganda, and counteractivities.

Their sophisticated digital literacy skills helped Gen Z easily call out the governmental propaganda that described the proposed “foreign agent” law as an analogue of “American” legislation allegedly motivated primarily by “transparency“ rather than by a desire to control civil society. These skills also helped Gen Z self-organize, communicate, and coordinate civil activities, including protests, giving young protesters confidence and persuasive ability. Thus, it can be said that one of the main strengths of Gen Z is their creative and knowledge-based vision of protest as a phenomenon, which makes their activism more resilient in the face of a diversity of propaganda instruments.

The European Idea as a Red Line

The main trigger of the Gen Z protests in March 2023 was the growing threat to Georgia’s European future. The values of the Georgian Gen Z can be illustrated as a dichotomy between European values, which they see as the only future for Georgia, and Russification, which they see as posing a threat to these values. For Georgian youth, this is a zero-sum game: a decline in one means an automatic increase in the other. When explaining “Russification,” young people typically refer to the adoption of the political and social model that exists in Russia, which would produce a fundamental shift away from Georgia’s aspiring democracy and toward Russian-style authoritarianism.

For members of Georgia’s Gen Z, the European cultural space feels closer and more authentic. They were born into a Georgia that was undergoing a slow but constant process of Europeanization and Westernization. Consequently, they unequivocally rejected the Russian-style draft law that endangered Georgia’s place in this space. In comparison to other antidemocratic developments occurring in the country, Gen Z perceived a clearer threat of “Russification” in this bill, making this generation more vocal in March 2023.

Gen Z at the Ballot Box

The social ascent of Gen Z is making a difference not just on the streets, but also at the ballot box. As they slowly reach voting age, their arrival will tilt the electoral preferences of the Georgian population heavily in favor of pro-Western parties and against pro-Russian and social-conservative ones. According to GeoStat, the share of youth (aged 10-19) in the electorate/population will increase by approximately 207,800 by the 2024 parliamentary elections and by a total of 460,400 by the 2028 elections. This is a considerable share, capable of making a meaningful difference in electoral outcomes as this decade progresses.

As a general rule, electoral turnout is lower among youth, but the March 2023 protests demonstrated that this segment of society can be politically activated if triggered by antidemocratic deviations by the ruling party.

Conclusion

The emergence of Gen Z on Georgia’s protest scene exemplifies the significant impact that a digitally literate, educated youth can have on strengthening the country’s democratic resilience. A high level of digital literacy, political non-partisanship, and decentralized yet well-coordinated acts of civil resistance have proven to be the right mix to garner further public support and successfully challenge the government’s authoritarian transgressions. Moreover, the predominantly European orientation of Gen Z could also transform the electoral climate in Georgia in favor of pro-EU and pro-reform political parties as this generation reaches voting age in the coming years.

However, the Georgian Gen Z also faces the daunting task of dealing with a heavy legacy. Its emergence on the political scene is occurring at a challenging moment. Georgia’s domestic politics have been paralyzed for years by the mutual enmity between a ruling regime focused on self-preservation and a self-centered, recklessly ignorant opposition camp. Consequently, a significant portion of the population appears increasingly nihilistic and disengaged, displaying no affiliation with any political party, as evidenced by various public opinion surveys. The negative implications of party-led radicalization are also felt beyond Georgia’s borders. The country’s democratic reforms appear to be stalled, and Tbilisi’s relationships with Western partners are strained.

Gen Z alone cannot resolve all these issues. However, it can undoubtedly play a positive role in Georgia’s political dynamics by acting as a guardian of the nation’s democratic and European future.

Appendix:

Focus Group 1: International Black Sea University, Tbilisi, Georgia

- School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, female;

- School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, female;

- School of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, Journalism BA program, first course, male;

- School of Business, BA Program of Economics, second course, male;

- School of Business, BA Program of Management, second course, female.

Focus Group 2: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, male;

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, male;

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, male;

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, female;

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, female;

- Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, International Relations BA program, fourth course, female.

🔗 Policy Memo in Georgian – Policy Memo #67 | April 2023

© Photo Credit: Mtavari TV