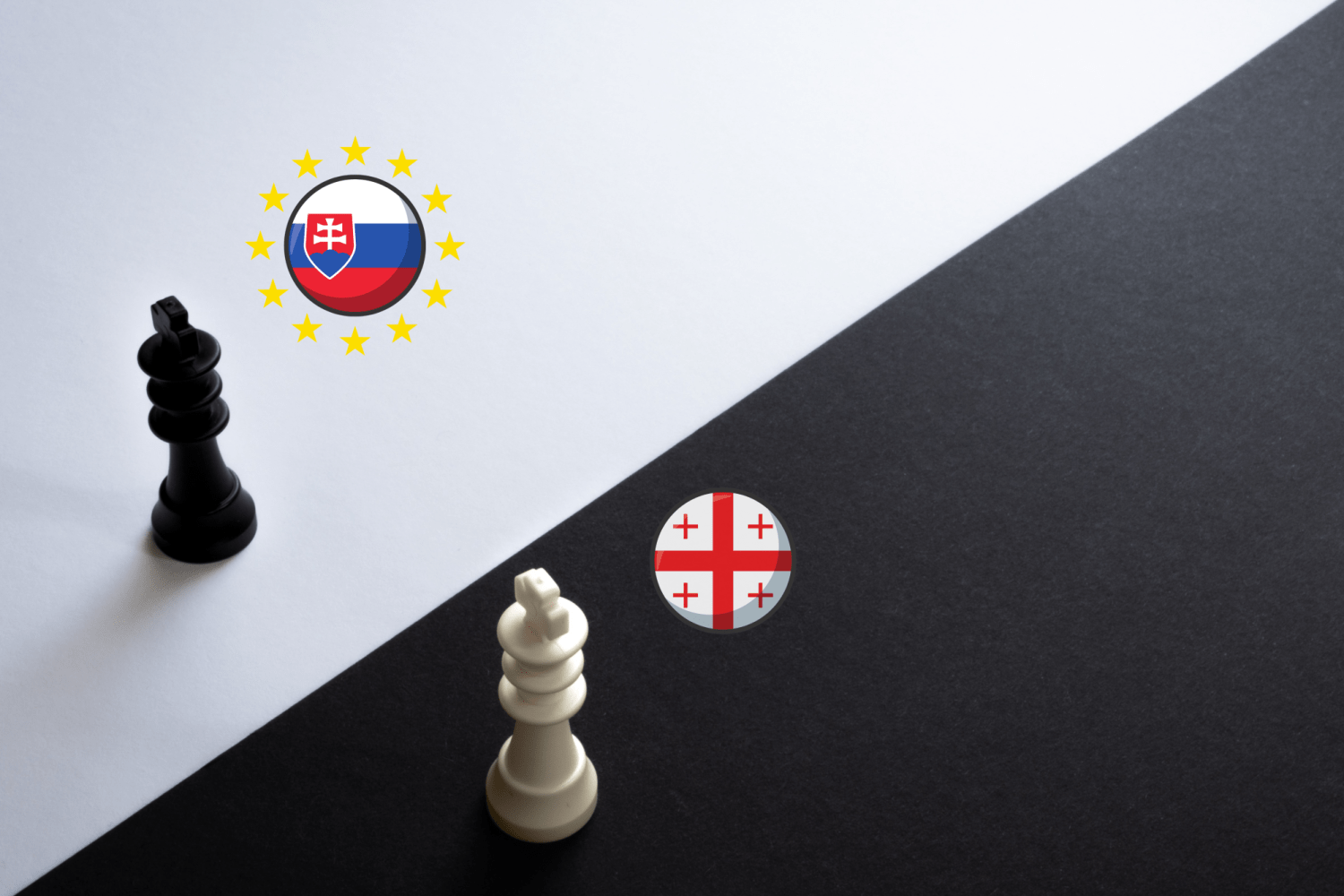

Georgia has to overcome serious internal and external obstacles on its path towards European integration. Similar obstacles to those Georgia is struggling with were also faced by a number of current EU member states in their process of Europeanization. Denying EU candidate status to a state and instead applying with conditionality is an accepted practice within the EU. Considering the current situation, Georgia bears very close resemblance to that of Slovakia at the time when it was denied candidate status due to undemocratic governance. The assessment of both countries by the Copenhagen criteria was most critical in the area of political conditions that imply failures in democracy, human rights, and the stability of institutions. It is therefore interesting to compare the state of affairs of these two countries on their path towards European integration and analyze how Slovakia dealt with the challenges mentioned above, whether the experience of Slovakia can be used as an example of Georgian European integration.

Confrontation between the government and the president

In 1997, Slovakia was denied candidate status due to a number of factors, some of which are relevant to Georgia’s case. Among other factors causing barriers to entry on an institutional level, one should focus their attention on the government’s disrespect for the sitting president and their attempts to delegitimize the institution of governance. Much like in Georgia, the president of Slovakia enjoyed support from the ruling party in 1992. Soon after his election, however, he decided to take unanimous decisions without the consent of the party, which ultimately led to tensions between Prime Minister Vladimír Mečiar and President Michal Kováč. In his annual address to the parliament, the president accused the prime minister of concentrating powers in his hands and of using state revenues for financing his own political party. Tensions resulted in the further curbing of the nominal powers of the president. Attempts to confine the president within certain limits have been undertaken in Georgia too. For example, the government prevented the president from having international visits and when she disobeyed, decided to lodge a complaint with the constitutional court, but at the end of the day, changed its mind. However, the government lodged a complaint against the president on other grounds, in particular for hindering the appointment of ambassadors. One may say that the situation in Georgia is more precarious than it was in Slovakia, because in Georgia the aforementioned confrontation was preceded by a two-year long political crisis. All that was further aggravated by a war in Ukraine and a refusal of the parliamentary majority to the president’s request to call an extraordinary parliamentary session on the topic of Ukraine and thus, belittling the institute of president. It should be noted, however, that neither president performed a role of consolidators of society in Slovakia or Georgia, because initially, both of them were supported by the ruling parties. Hence, a support of society to them was conditioned by a sympathy of society towards the ruling team.

To analyze the situation in these two countries, a table below shows indicators of Slovakia and Georgia of the time when the European Commission issued recommendations against granting them the EU candidate status.

Table 1: Democracy, freedom and corruption indices for Slovakia in 1997 and Georgia in 2022:

Source: The data obtained from official webpages of Freedom House, Polity IV, Economist EIU, Transparency International, RSF Reporting Without Boders-, Civil.ge . Slovakia 1997/Georgia 2022. 2022.

Source: The data obtained from official webpages of Freedom House, Polity IV, Economist EIU, Transparency International, RSF Reporting Without Boders-, Civil.ge . Slovakia 1997/Georgia 2022. 2022.

Political Conflict and Abuse of Official Powers

A flagrant example of abuse of power by Slovakia’s ruling team on the institutional level was the vote for the expulsion of a former party member from the legislature after he left the ruling party, the Movement for a Democratic Slovakia. Such precedent was set in Georgia too when the parliament stripped one of opposition leaders of his MP status after the court found him guilty of fraud, which has been disputed to date; while another MP was accused of abuse of official powers. Such precedents are mainly a result of personal confrontation or political conflict and they adversely affect electoral attitudes towards the ruling or opposition actors as well as the international image of a country. Of course, the aforementioned events did not go unnoticed by relevant EU institutions.

In 1997, the EU Council took a decision not to grant candidate status to Slovakia because the ruling party of Slovakia abused power, exerted influence on the judiciary, and disrespected the political opposition. In particular, on 23-24 May 1997, Slovakia held a referendum; one of four referendum questions was initiated by the opposition parties and concerned the introduction of the rule of direct presidential election – as according to the 1992 constitutional amendments, the president was appointed by the government. It is worth noting that the opposition parties succeeded in pushing this initiative via the president thanks to over half a million signatures which they collected. However, to enhance its power, the ruling party applied to the court for removing the aforementioned question from the list of referendum questions. Ultimately the court did not rule in favor of the government, but the ruling party arbitrarily removed the question at the last moment.

The above-described precedent triggered protest among the population and a large segment of it boycotted the referendum. Consequently , the referendum did not bring about any result. Even more, the fiasco of the president and the opposition party as well as the illegal action of the government, has had a negative effect on the country’s membership to NATO because the first referendum question was about the support to NATO membership and the referendum fell through. The prime minister tried to sell the situation as if the country did not lose anything, alleging that NATO was not ready for the enlargement of the Alliance regardless. For the purpose of comparison, it should be said that a similar rhetoric was applied by the Georgian government after the European Commission issued its conclusion to refrain from granting Georgia a candidate status. Leaders of the government said that had it not been for Ukraine, Georgia would not have submitted the membership application until 2024 and therefore, there was nothing tragic about the EU assessment. At the same time, however, they put the blame of not granting the candidate status to Georgia on the negative effects of the opposition parties.

Instead of overcoming the political polarization, which is the first condition of the 12-point recommendation from the European Commission, the political elite continues to confront each other. To save the image of the country, the Georgian population is undertaking efforts, for the second time now, to rectify the mistakes made by the political class. At first, society managed to save the country’s image by staging massive rallies in solidarity with Ukraine, collecting humanitarian aid for Ukrainians and voluntarily helping them. Another time, thanks to tremendous efforts of civil society and young activists, a rally of unprecedented scale was held in support of the country’s European integration. Those solidarity acts of the society attracted international attention. Nonetheless, it must be noted that the foreign course of Euro-Atlantic integration cannot be maintained by rallies of Georgian population alone, but requires a high degree of institutional responsibility which has not been seen so far.

Restriction of independence of the judiciary

In terms of independence of the judiciary , challenges in Slovakia in the 1990s were no less serious than those of Georgia. In particular, over the period between 1993 and 1997, during the premiership of Vladimír Mečiar, the judiciary in Slovakia was controlled by the Ministry of Justice and the Parliament and the government directly decided on the appointment and promotion of judges. Loyalty of judges to the government were also conditioned by the fact that judges were given a four-year probation period. During that period, the judges spared no effort to gain the disposition of the government in order to be granted life-long tenure. The situation is similar in Georgia where judges were appointed to the supreme court for life in an expedited manner regardless of harsh criticism, different recommendations of international partners and national lawyers. Mistrust in judiciary is one of the most serious challenges faced by Georgia; in case of Slovakia, the similar situation had not improved until after the change in government through elections, because the government of that time lacked a political will to ensure transparency of the judiciary. Judging by the international practice, the most workable option in this regard is the pressure from international organizations and the introduction of a stricter monitoring mechanism, all of which is important in case of Georgia, especially in relation to the rule of appointment of judges.

Challenges related to freedom of press

Identifying a degree of independence of media is one of main measurements for assessing the level of democracy and freedom of press both in Slovakia and Georgia. It must be noted, however, that the results of assessment of press freedom in Slovakia were much lighter than those in Georgia. At that time, the media in Slovakia was opposed to using mechanisms of verbal confrontation. For example, targets of verbal attacks of the prime minister Vladimír Mečiar’s government were two TV channels, SME and Markiza, only because they gradually distanced themselves from the ruling party towards which those media outlets, earlier, had pursued a more loyal editorial policy. In response to scathing coverage of the government activity, the government suppressed the frequency of independent radio station, Radio Twist. Like the government of Georgia, the Slovak government of that time turned several TV channels into a weapon of political indoctrination, which spread propaganda information to discredit the president having turned his back on the ruling party, the political opposition and the media outlets that were critical of the government. During the Mečiar rule, a press freedom index notably deteriorated in Slovakia and the media environment was downgraded to “partly free” in the 1997 Freedom House report. Nevertheless, independent media outlets still continued to operate and played an important role in helping citizens make informed decisions. That contributed to the process of changing the government through the parliamentary election in 1998; after the election, within a month’s time, the European Commission issued a recommendation to award the status of EU candidate state to Slovakia while in 1999, formal accession negotiations were launched which culminated in Slovakia’s accession to the EU in 2004.

Media in Georgia can also greatly contribute to the cause of the country’s European integration; however, because of extreme polarization, a politically biased coverage by certain media outlets may have a negative effect on the process of Europeanization. At the same time, it should be noted that frequent physical assaults on media in recent years and inaction of relevant state agencies to protect journalists’ rights and punish culprits have invited scathing criticism from various EU institutions, which also adversely affects the process of European integration. Nonetheless, it must be noted that critical media organizations still manage to continue operation and to deliver alternative information to society in Georgia.

Factors that helped deconstruct illiberal tendencies in Slovakia since 1998: a lesson for Georgia

The refusal of the EU Council to award EU candidate status to Slovakia triggered the formation of critical attitudes towards the government and intensive mobilization of Slovak society. Earlier, a segment of society had failed to realize a gradual reinforcement of authoritarian tendencies within the government. Civil society, media and international actors largely contributed to the deconstruction of illiberal tendencies. The political opposition, which was not much trusted by the electorate at that time, also played a role, though less significant, in this process. The mobilization of the population of Slovakia was largely induced by the fear of becoming isolated and marginalized from Western institutions. The political opposition used that momentum reasonably too and by setting up a coalition of four political parties gained the parliamentary majority in the 1998 election and formed a new government led by Mikuláš Dzurinda. A populist rhetoric of the Mečiar government, which tried to influence society by kindling nationalist dignity and sentiments and portraying opponents as enemies, was outweighed by a fear of economic and international marginalization.

Real prospects of EU integration opened up for Slovakia only after the change in power, displaying the willingness to implement reforms and taking actual steps. The situation in the case of Georgia is grave because the next election is only due in 2024. Therefore, the pressure emanating from the tension among society must be exerted on the incumbent authorities for the aim of effective implementation of 12-point recommendations within a six-month term. As regards the demand for early election, it requires a broad popular consolidation and immense financial or administrative resources. Furthermore, in terms of electoral reform for holding the election, a number of recommendations need to be accommodated, including those implied by the Charles Michel agreement as without implementing them it would be difficult to conduct elections in a free and fair environment. In order to improve the situation and reinstate Georgia to the so-called trio format, the most important factor is to toughen the control over government’s activity to the maximum extent on local as well as international levels. A joint effort of civil society is also required to support the implementation of various institutional reforms. Furthermore, it is no less important for opposition political parties to consolidate around European values, to work on the enhancement of electoral support for the next election and strengthen relationships with Western partners. The application of conditionality to Georgia on its path towards European integration may nudge Georgian population, towards a stronger mobilization and adoption of a more critical stance towards each and every decision of the political elite. These changes would increase civic control over, and accountability of, the government as well as political opposition.