Author

Jelger Groeneveld

Jelger Groeneveld

Board Member, International Security & Defense division,

D66 liberal democratic party, Netherlands

Would the Netherlands be the first domino to fall to populism in mainland Europe’s election season? That was the main focus of international media last week, despite the fact that, in the Netherlands, elections tend to be rather dull.

Following the Brexit referendum in the UK and Donald Trump’s election in the US, national elections in key EU member states raised questions of whether the EU’s future is at stake in 2017. After all, the Netherlands preceded the UK in April 2016 with a referendum vote to reject the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement—after a long and fierce populist campaign against the Association Agreement that had parallels with the “out” campaign in Britain.

Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the incumbent conservative-liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD)—the party which came out ahead once again last week—claimed in his victory speech that the Netherlands “didn’t succumb to the wrong kind of populism.” Indeed, emphasis on “wrong kind” of populism is correct, as populism has gained roots in mainstream politics in the Netherlands. So, what happened?

It was widely projected that outspoken anti-Islam, anti-EU populist leader Geert Wilders of the Party for Freedom (PVV) would win the elections by gaining the largest faction in Parliament. A PVV victory would give it the initiative to form a coalition government with Wilders as prime minister, a position to which he openly aspired. He is close with French Front National leader Marine Le Pen, who will run for president this April.

That didn’t happen. Wilders’ PVV party slipped in the polls after January, primarily due to his absence from public debates and withdrawing from commitments on several occasions. In a tactical decision in mid-January, Prime Minister Rutte explicitly ruled out the prospect of governing with the PVV, something he had previously left open as “highly unlikely.” His party would be the obvious pick as a coalition partner for Wilders. Many people, then, seemed to realize that a vote for Wilders would be a vote lost, as all other major parties rejected the PVV as well.

The Christian Democrats (CDA) claimed the space PVV left in the electorate, picking up the nationalist agenda with proposals such as banning dual citizenship, mandating public service for youth and singing of the national anthem in school, and emphasizing the importance of Christian values and norms for social progress and equality. An ironic contradiction if one remembers that the CDA actively blocked any attempts at liberal progress during the 20th century.

During the recent diplomatic spat between the Netherlands and Turkey, the CDA even suggested that the EU tear apart its Association Agreement with Turkey. Here, the VVD made a positive impression with voters. The Prime Minister showed leadership by taking bold moves against Turkish cabinet members who tried to enter the country against Dutch instructions (“don’t mess with the Dutch”), giving a final boost to the Prime Minister and his party to help them win the elections.

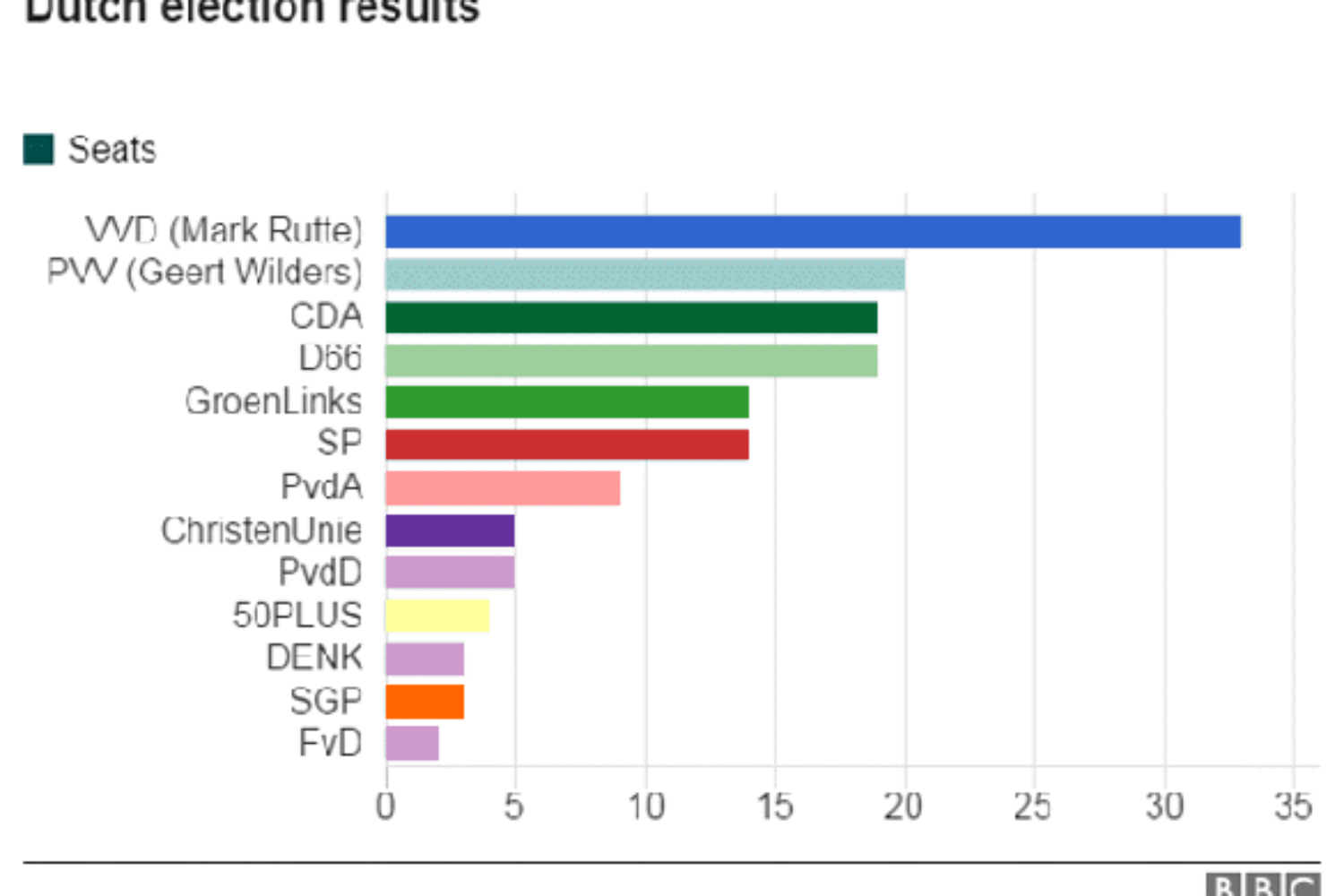

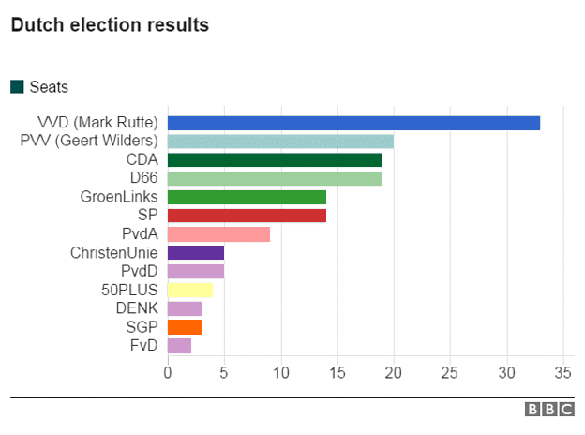

The formation of a new government will kick off this week, an event which typically involves a lengthy dance around the tables. All potential coalition partners will be reviewed for what they are (and aren’t) willing to give. Traditionally, the process takes months. The election result is the most fractured since the early 1970s with 12 parties winning seats in parliament. The participation of at least four parties is necessary to form a government backed by a parliamentary majority.

Photo: BBC

There is widespread consensus that the core of the new government will be the conservative-liberal VVD, the Christian Democrats, and the social-liberal D66 party, which together account for 71 of 150 seats. Three parties are candidates to round out the coalition. The incumbent Labour Party (PvdA) is an unlikely choice as they faced a massive defeat, falling from 38 to 9 seats, paying the price for governing the country following the economic crisis along with the liberals. Other candidates are the Christian Union and the Green Lefts; the latter winning a record 14 seats.

Whatever the composition of the government, it won’t have a major impact on Dutch foreign policy. Prime Minister Rutte has fiercely defended the EU-Turkey refugee deal that he and his deputy minister for immigration brokered during the Dutch EU presidency in 2016. To keep that deal alive, the EU must stick to formal continuation of EU accession and visa waiver talks, something that looks like little more than a charade given domestic developments in Turkey.

Similar refugee deals with African countries are being promoted by Rutte’s VVD party. The VVD’s liberal partner D66, which is part of the same European ALDE family of parties, opposes such agreements as they skirt or violate UN treaties and raise other moral questions. The question is whether D66 can drive a reversal of that policy. D66 seeks to progressively democratize the EU, transfer mandates to Brussels, and invest in relationships with the EU’s neighbors, but many currently oppose such Europhile measures.

Calls for a so-called “two-speed EU” may pick up in the Dutch foreign policy establishment, however. It was roughly 20 years ago that then-VVD leader Frits Bolkestein, the former employer of Geert Wilders, first propagated the idea. D66 has opposed it so far, but in its latest election program and doctrine update it recognized that it may be an option.

Not much will change for Eastern Partnership countries. Both Ukraine and Georgia will enjoy visa-free travel in the Schengen area, and Association Agreements are firmly in place. Several weeks ago, the Dutch lower house voted in favor of ratifying the Association Agreement with Ukraine after Prime Minister Rutte negotiated an appendix to the agreement addressing the major concerns of its Dutch sceptics. The upper house still has to vote on ratification, a tactical and crucial point as the CDA voted against it in the lower house for public relations reasons, despite being in favor of the treaty itself (and against referendums on ratification). Ratification of the treaty is expected. Furthermore, the new government is not expected to change its policy regarding sanctions against Russia.

Conclusively, it can be expected that Dutch foreign policy will be business as usual: EU and NATO oriented, critical of the political regimes in Turkey and Russia, and supporting partnerships with countries of the willing on the EU’s periphery.