Bidzina Lebanidze[1] Shota Kakabadze[2]

The Georgian Orthodox Church (GOC) has long served as both a social glue in Georgia and a significant marker of the contemporary Georgian national identity. However, over the last few years, the GOC has been drifting away from its historical position of moral superiority and political neutrality towards something more radical. This was confirmed by the involvement of some clergy members in recent violent anti-LGBTQI protests and the adoption of anti-liberal and anti-Western language by high functionaries within the Church to an extent never before seen. These events point to a creeping radicalization of the GOC – an alarming trend that can ultimately lead to an identity crisis of Georgian society as well as undermine its social cohesion.

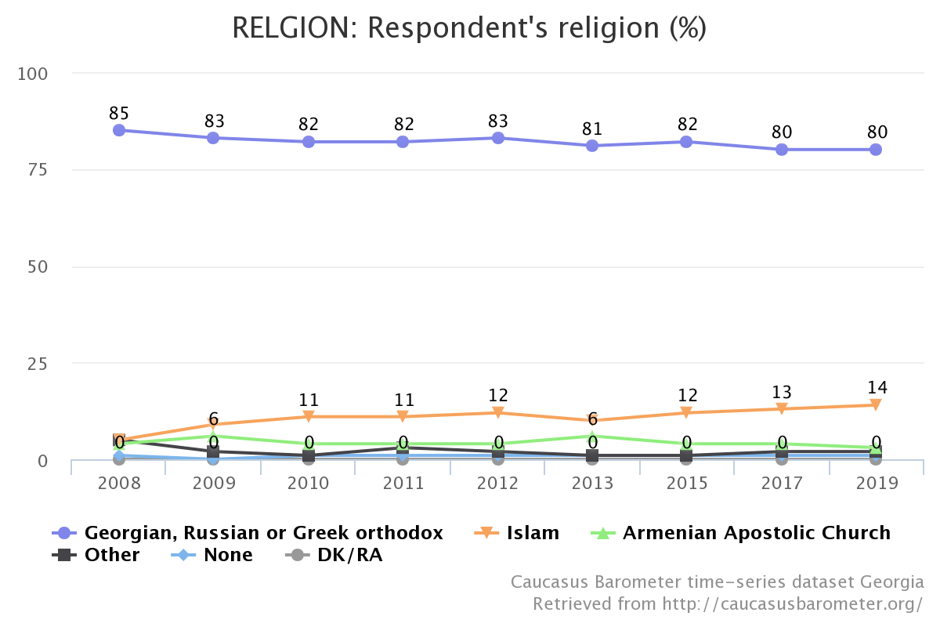

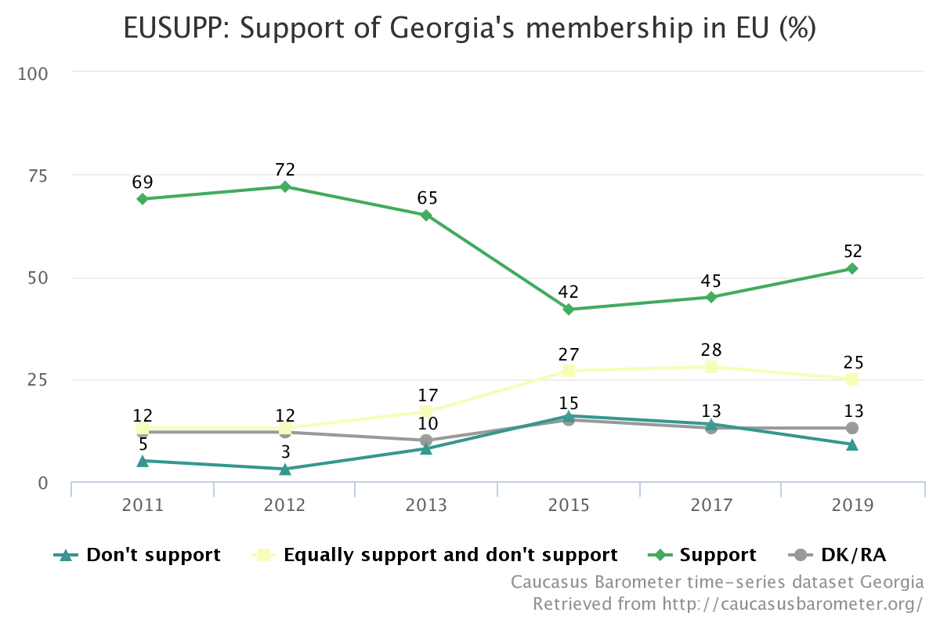

There are two major ideas around which Georgian identity was built after the end of the Cold War: Orthodox Christianity and the “Return to the European family “. Data from the Caucasus Barometer illustrate that an absolute majority of Georgians consider themselves Orthodox Christians (Figure 1), while Figure 2 suggests that support for Georgia’s possible membership in the EU has been consistently high among Georgian citizens.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

These two pillars of Georgia’s national identity coexisted peacefully for the last two decades – this is thanks in part to the flexibility of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The GOC always managed to strike a difficult balance between traditional values on the one hand, and Georgia’s European orientation and path towards western integration on the other. The Patriarch of Georgia personally expressed his support for the EU membership amid the use of anti-Western discourse by several influential clergymen.

These two pillars of Georgia’s national identity coexisted peacefully for the last two decades – this is thanks in part to the flexibility of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The GOC always managed to strike a difficult balance between traditional values on the one hand, and Georgia’s European orientation and path towards western integration on the other. The Patriarch of Georgia personally expressed his support for the EU membership amid the use of anti-Western discourse by several influential clergymen.

What happened to the Church? From balancer to bully

Despite the official support of Georgia’s European future by the GOC, the latter’s position on many issues remains controversial as high clergymen from the Church have influenced various state policies. Between their successful opposition to the introduction of new subjects in schools and their attempt to prevent the passing of an anti-discrimination bill in defense of minority rights, the Church’s negative political impact is clear. On several occasions, the GOC has also inspired homophobic groups to actively suppress actions in support of the LGBTQI community.

Nonetheless, up to now, the Church has never crossed any social or political red lines regarding Georgia’s European choice. At least formally, the patriarchate has always supported Georgia’s desire for European integration and the language of their key functionaries has always been supportive of Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic prospects. The EU itself also acknowledged the important standing of the GOC and started to involve it more closely in political dialogue. A delegation from the Georgian Orthodox Church even made an official visit to Brussels in 2019.

Yet, a dramatic shift has taken place over the last few years within the GOC. The radical branch of the clergy, including influential bishops, started engaging with anti-European, anti-Western, and anti-Liberal discourse en masse. While the Church has historically opposed the social emancipation of the LGBTQI community via the institutionalization of their rights and liberties, the massive increase in hate speech among the clergy has been alarming.

For outside observers, it seems that the radical, anti-European wing has consolidated its influence within the GOC, and moderate voices are being silenced. What is even more concerning is that by actively participating in political processes the GOC has also further moved away from a position as neutral arbiter and has become a part of the radical political polarization between the government and opposition and their supporters. However, the Church’s recent actions are counter-productive: while the majority of Georgian citizens are anti-LGBTQI this issue is never one of the main concerns of the population – people are far more worried about the state of the economy, access to or quality of healthcare, or unemployment. Moreover, as the result of the participation of several clergymen in the recent anti LGBTQI protests and violent attacks on journalists, the GOC might be losing the moral high ground it has naturally enjoyed in a traditional society like Georgia.

In a broader sense, if this trend continues, it poses a danger to Georgia’s European future as it might go against the particular construction of Georgian national identity by the GOC. This will have long-term negative consequences both for the GOC as an institution and for Georgia’s liberal-democratic future. The short-term implications are already apparent, with foreign tourists cancelling their trips to Georgia. However only time will tell how such negative developments are going to affect Georgia’s international credibility in the future.

Radicalization will harm GOC

All things considered, there are several reasons why the anti-European radical discourse is not in the long-term interest of the GOC and most likely will undermine the Church’s influence.

Georgia’s foreign policy choice is not only about values and traditions, but about the concrete material benefits and economic incentives coming from the European Union, that directly translates into the well-being of ordinary Georgians. Hence, the GOC’s anti-western discourse will lose its influence in the long run as the cost of souring relations with Brussels is extremely high.

Additionally, when the time comes for the current leadership of the GOC to change, an internal power struggle might take place – as the recent alleged assassination attempt case illustrates. Another parallel issue is the cult of personality surrounding Patriarch Ilia II – “the most trusted man in Georgia” – which means that a certain amount of popularity of the Church relies on the current leadership.

Furthermore, the radicalization of the Church will probably also result in an exodus of its educated, urban, and well-off followers. Various sets of data show that Georgians are not religious people in a theological sense but their attachment to Christianity has a symbolic, civic notion – it is understood as a centrepiece of the Georgian national identity.[3] However, should Europeanness and belonging to the GOC become mutually exclusive and if the Patriarchate, intentionally or unintentionally, further adopts anti-Western narratives this will cut many social bonds and further alienate those followers they cannot afford to lose – especially from the youth and urban populations. If the church goes this way, it will have a difficult time remaining the most popular and trusted institution in the country.

To conclude, the anti-European radicalization of the GOC does not benefit either the church itself or the country. The GOC is not obliged and neither is it expected from this institution to accept the LGBTQI parades or anything it finds morally wrong. However, clergymen need to find ways to communicate their concerns with Georgian society in a peaceful, civil, and non-violent way. Most importantly, the Patriarchate should ensure that the GOC, or groups and organisations associated with the latter are not opposed to the idea of Georgia’s European integration – as it will not only harm Georgia’s liberal democracy and its European future – but in the long run it, will also undermine the church’s standing as the most popular and influential institution in the country.

[1] Senior Analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP), a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Slavic Languages and Caucasus Studies at the Friedrich Schiller University Jena and Associate Professor of International Relations at the Ilia State University.

[2] Junior Policy Analyst at the Georgian Institute of Politics.

[3] For instance, according to World Values Survey, 78.5% of Georgians agree that „the basic meaning of religion” is “to do good to other people” while only 18.6% say it means “to follow religious norms and ceremonies”. Source: World Values Survey. 2021. “WV6 Results Georgia 2014 v20180912“. Available at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Accessed: 19 July 2021.