Author

Florent Parmentier

Florent Parmentier – PhD, is Secretary-General of the CEVIPOF – Centre of Political Research – at Sciences Po. He teaches geopolitics and strategic foresight and regularly intervenes in the media.

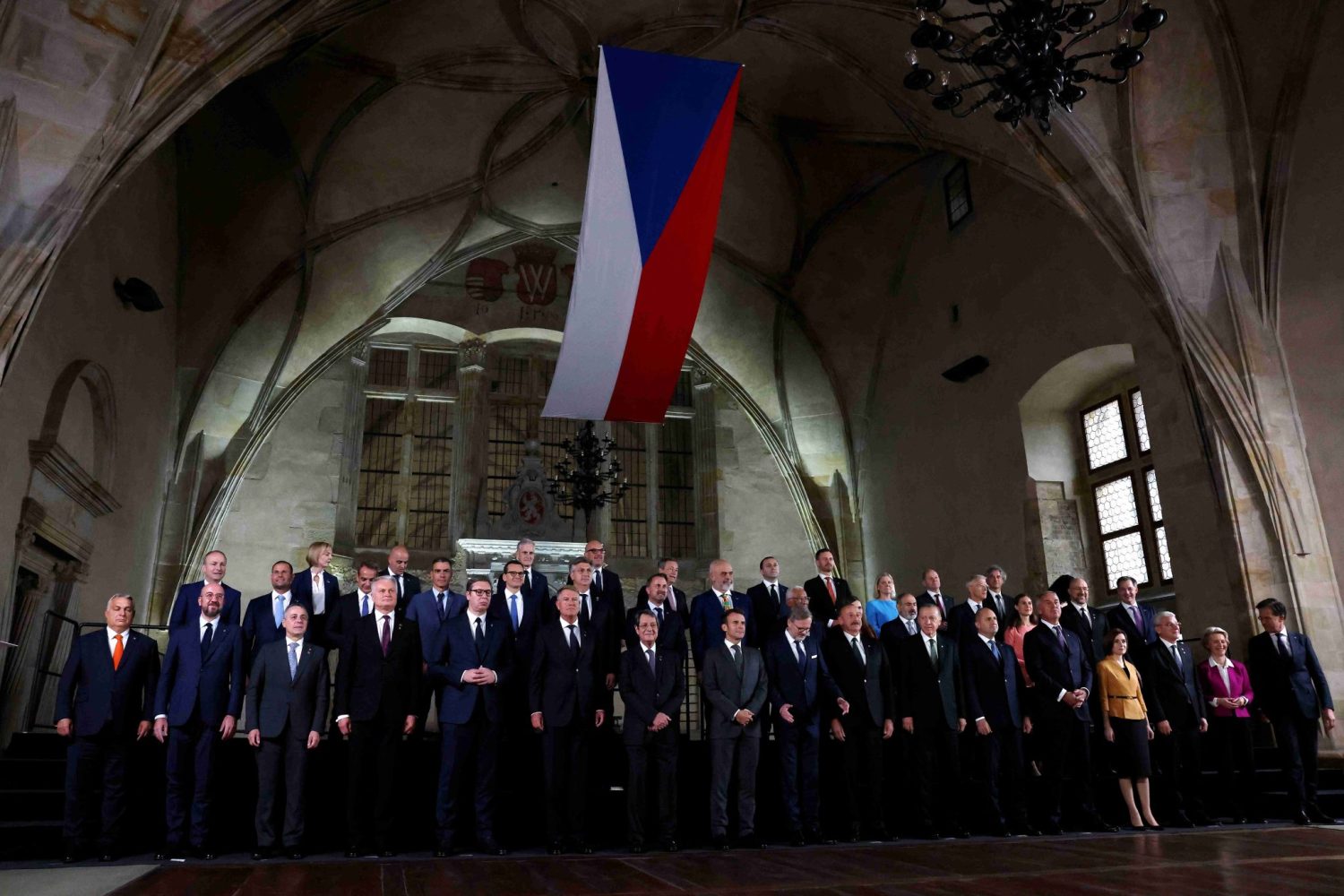

On May 9, President Macron presented his project of creating a ‘European Political Community’ (EPC) during his speech at the European Parliament in Strasburg. Despite an initial period of skepticism, this idea was approved during European Council on 23-24 June, the same day the European perspective of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia was recognized. The EPC was officially launched on October 6, in Prague Castle, including 44 delegations of countries inside and outside the EU.

The EPC aims to organize Europe from a political point of view without making everything rest exclusively on the EU, with the exclusion of Russia and Belarus. As a participating country in this platform, Georgia should use this format to ‘speed up’ the process of Georgia’s integration into the EU through political cooperation.

The EPC is not a new organization, not a substitute for enlargement or a placebo: it is an intergovernmental forum that should help foster cooperation and achieve convergence for peace and stability on the European continent.

Not a new organization, but an intergovernmental community

The EPC is inspired by a historical precedent imagined by François Mitterrand and co-designed with the then-President of Czechoslovakia Vaclav Havel, namely the European confederation. At the time, in 1989-1991, this project, based on a concentric circles approach, was built to respond to three major challenges: peaceful exit from the Cold War, German unification within the framework of the European Community (i.e., without modifying the borders) and the inability of the European Economic Community, composed by 12 member states, to integrate the newly emancipated countries. Alas, the proposal did not work out due to major flaws alienating support in Central and Eastern Europe: it kept the USSR in, the USA out and looked like a maneuver to avoid any quick enlargement.

Macron’s proposal happened at a moment of historical bifurcation due to the Russian war in Ukraine. Macron incidentally then held the EU presidency, giving him more room to take leadership in a time of crisis. It is based on an intergovernmental approach, with one political leader for each country, in addition to the presidents of the European Commission and European Council. Rather than creating a new organization, the rationale behind the EPC lies in bilateral meetings, considered more important than non-binding official resolutions. Instead of a new acronym or relying on a new secretariat, the EPC’s approach is very similar to the G20, an agile intergovernmental forum focused on the governance of the global economy. As the results of the current discussions on reforming the EU system are still uncertain, the adaptive model of the G20 is attractive.

As an intergovernmental forum, the EPC should avoid the risk of irrelevance. Hence, it should be able to rely on sometimes overlapping clubs, such as the Council of Europe or the OSCE, rather than adding another organization to the existing political landscape. Another trap would be to follow the proposition of short-lived British Prime Minister Liz Truss, who proposed to rename it ‘European Political Forum’. A Community, by contrast with a forum, implies a sense of belonging to the same democratic area and sharing the same values and destiny. In this case, the EPC might become a new kind of EU-Asia or EU-African annual forum, which does not deliver much in terms of outcomes.

Not a substitute for enlargement, but an acceleration of cooperation

One of the reasons why the original ‘European confederation’ failed was the perception that Mitterrand’s proposal seemed to postpone any perspective of enlargement for Central and Eastern candidates anytime soon. Meanwhile, through the 1990s and 2000s, enlargement was considered the most efficient EU policy, anchoring European values in many countries. However, it is equally true that enlargement proves to be more difficult to achieve in the case of the six countries of South-Eastern Europe (Serbia, Montenegro, Albania, North Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo). The political stalemate has led to an ‘enlargement fatigue’, both in candidate countries as well as in current member states.

Because of the war in Ukraine, the enlargement game is back in town, with Ukraine and Moldova as frontrunners among the Eastern partners, while Georgia is lagging just behind. Alas, the process will not happen overnight. It should be clear that the EPC is not a substitute for enlargement: it should instead offer more room for cooperation for Georgia and other countries, provided they respect the key values defined in Article 2 of the Treaty of the European Union: human dignity, freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights. Participation in the EPC can be decoupled from granting the candidate country status. The EPC tries to fix the drawbacks existing in the enlargement process in South-Eastern Europe: as a ‘fast-track’ integration process does not exist new format should emerge to support reforms in candidate countries in the long run. Meanwhile, the EU institutions should reform themselves to adapt their functioning to an organization with 35 or more members.

Not a placebo, but concrete convergence

Too much like the EU for the UK, not enough like the EU for neighboring countries: institutional debates are one thing but coordinating our responses to critical threats is more important than ever today. The latter highlights the weakness and incompleteness of the continent’s security and defense architecture and its lack of articulation in critical strategic priorities (energy, climate, etc.). Therefore, EPC requires a redefinition of the relative roles of the Union and the Member States, and the involvement of neighboring countries in a unifying project. Otherwise, it may meet the same fate as the Union for the Mediterranean, an initiative by former French President Sarkozy which fell below expectations.

Convergence should happen first in the security sphere, at a time when Russia is attacking Ukraine. Security should be understood broadly, including energy, infrastructure, cyber security and human security. At the end of the war, Ukraine’s experience should be incorporated into European defense and strategic thinking. Consideration should also be given to measures aimed at strengthening the resilience of democracies in the face of hybrid threats, including Georgia. As regards energy and climate, the current energy crisis is an opportunity to realize an inclusive project associating energy independence (cutting relations with Russia) with climate transition (European Green Deal). Concrete projects on coordinated or joint infrastructures should set the EPC agenda, such as interconnectors in the North Sea and the Balkans, new relations with Norway and Azerbaijan or developing partnerships for green hydrogen. Finally, the Union has long considered its market as its greatest source of attractiveness. Even if its relative share of wealth in the world is still declining, it will remain a significant partner for all the members of the EPC in the foreseeable future. It is leverage to foster European values as economic, social and political convergences are linked.

Of course, a large gathering of countries such as the EPC does not come without internal contradictions. While most of the EPC members apply sanctions against Russia and Belarus, attitudes towards Turkey are more divisive, as Greece, Cyprus and Armenia now have tense relations with Ankara. In this perspective, the meeting between leaders of Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan is a good signal of what an intergovernmental community can achieve through socialization, with the perspective of establishing a civilian EU mission alongside Armenian-Azerbaijanis borders. In this case, the adaptive platform of the EPC complements the more institutionalized cooperation in the framework of the EaP.

It is probably too early to evaluate the success of the EPC, as Macron’s initiative has only organized one meeting so far, with many questions remaining. Yet, an indication might be that the next biannual summits are already planned in Moldova, Spain and UK.

As regards Georgia, the EPC offers an opportunity to cooperate with European partners to foster resilience vis-à-vis Russian threats, against the background of a diminishing presence of Western geopolitical partners. Associated with Ukraine and Moldova, Georgia can take the best of the EPC in its current form, and actively participate in its development.