Author

Givi Silagadze

Givi Silagadze[1]

Georgia approaches the decisive 2020 Parliamentary elections amid a shrinking national economy, the adjacent war in Nagorno-Karabakh, and an unprecedented public health crisis. The past year has been especially dramatic for the ruling Georgian Dream party. They failed to deliver the electoral reform which the party leader had unambiguously promised, triggering street demonstrations, a political crisis, and subsequent criticism from some of Georgia’s closest partners in the west. The political crisis was to some extent resolved when the main political parties of Georgia, with the facilitation of the diplomatic community, reached an agreementon March 8, 2020 about the system design for the 2020 election. However, just as this political crisis was wrapping itself up, the Covid-19 pandemic stole the show.

Considering the unusual circumstances surrounding upcoming election, it is not entirely clear what the election outcome will be and what it might mean for the country’s democratization process.

Is GD well-positioned to secure a third term?

Most experts believe that Georgian Dream (GD) will prevail in the proportional part of the 2020 Elections, but it is unclear if they will garner sufficient votes to form a government. There are three more-or-less likely scenarios which can play out: first, GD will get a sufficient number of seats to form a government singlehandedly; second, GD will need to coalesce with a smaller party to form a government; and finally, opposition parties will get enough seats to unite and form a government with United National Movement (UNM) at the center of the coalition. Considering the situation in the country as it is now, the latter scenario seems least likely due to the following reasons:

Covid-19: No appealing alternatives from the opposition and political instrumentalization of the pandemic by the ruling party

The Covid-19 pandemic has, and will continue to have, a huge impact on socio-economic and political processes in Georgia. Despite its significance, most opposition parties have failed to propose real alternatives to GD’s handling the virus and some of the leading opposition parties barely mention Covid-19 in their pre-election programs.

GD has managed (at least until the recent upshift in daily cases) to sell a narrative that the government has successfully contained the virus. In June-July 2020, 83% of the public rated prime minister Giorgi Gakharia’s performance in response to pandemic as well (49%) or very well (34%). In August, 53% of the Georgian population assessed the aid by the government as sufficient (11%) or somewhat sufficient (42%).

GD tries to proactively associate itself with a “successful handling of the pandemic”. Principal public health officials, who have been in the forefront of tackling the virus, have attended the party’s political events and some of them have openly declared their support for GD. What this might suggest is that GD has tried to translate the public health crisis into political gains.

It must be noted that daily new cases of infections has risen dramatically in the past few weeks. Considering that the government imposed a curfew in response to a few dozens of cases in the Spring, GD’s current, lighter, reaction to hundreds of new daily cases might be explained by potentially high economic costs of a lockdown as well as by the approaching elections. If GD postpones the elections, it might prove politically disadvantageous due to the quickly deteriorating socio-economic conditions in the country. As for the upcoming elections, unless Georgia experiences a total breakdown of its health institutions due to overloaded hospitals, GD will probably manage to translate the pandemic into its political gain.

Inclinations of the Opposition – mostly unappealing policy alternatives, factionalism and a turn to bipolarity, again

Georgian and international experts do not see substantial policy alternatives coming from the opposition. It would be inaccurate to claim that the opposition does not put any alternatives on the table. One of the opposition parties which explicitly tries to defy the bipolar pattern of Georgian politics has offered a comprehensive economic reconstruction plan, but they have failed to gain momentum in Georgian politics. Furthermore, recent consultations between the major opposition parties resulted in two joint agreements about reforms to Georgia’s justice, economic and education systems. However, some opposition parties somewhat downplay these agreements’ importance or, at least, do not make it their main agenda when communicating with the public. Finally, for most of the voters, the image of the party leader seems to be more important than a party’s promises or platform.

In contrast to the first half of 2020, when the opposition spoke in essentially one voice, opposition parties during the pre-election campaign have frequently found themselves at each other’s throats. For instance, one of the leaders from the opposition has claimed that UNM breached the cooperation agreement. Also, after UNM named ex-president Saakashvili as their candidate for prime minister, some of the opposition parties criticized the decision and made an explicit commitment not to support the UNM’s candidacy. Overall, it seems that Saakashvili is, arguably, one of the least consolidating figures for the opposition at this moment.

Finally, by trying to put the ex-president Saakashvili to the forefront of the opposition, the UNM-led coalition, “Strength in Unity,” forces the pre-election discourse to revolve around the two polarizing personalities – Saakashvili and Ivanishvili. The opposition should have learned from previous experience that this dichotomy gives the ruling party a decisive advantage. Despite the new electoral system which favors a pluralistic environment, and attempts from some of the opposition parties to defy the bipolar political pattern, the pre-election period is still expected to be largely dominated by a clash between the two personalities.

Possible Implications for Georgia’s Democratization Process

At this point it is not entirely clear what the balance of power will be after the election. If GD comes out victorious, it would be a novel phenomenon in Georgian political culture – a party in power for a third election cycle. This may be challenging for Georgia’s long term democratization process because opposition parties might lose faith in the ability to remove a governing party via elections. This may prove especially disheartening against the background of GD using administrative resources for political purposes, their huge financial advantage, and the ability to disseminate its vision more effectively than other parties.

Additionally, GD has overseen a process of democratic backsliding. In 2016 and 2017, Freedom House assigned Georgia a score of 64 (with 0 being the worst and 100 the best), in 2019 the organization gave Georgia a 61 and pointed outthat, “recent years have featured backsliding.” Moreover, a third term would perpetuate informal control over public institutions and continue to be a major characteristic of Georgia’s internal politics, which is at odds with democratic principles.

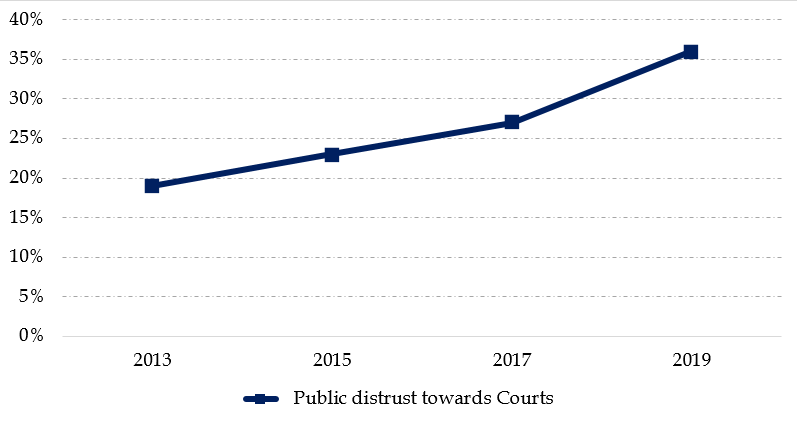

Finally, GD has continued acting controversially with regard to the judicial system. The EU, commenting on a newly adopted legislative amendment regarding the selection of supreme court judges, expressed regret that Georgia’s parliament did not take into account the opinion of the Venice Commission. Moreover, since GD acquired power in 2012, the public distrust of the court system has grown significantly (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Increasing distrust of the judiciary among the Georgian population

Source: Caucasus Research Resource Center. Caucasus Barometer. Available at: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/TRUCRTS/

Source: Caucasus Research Resource Center. Caucasus Barometer. Available at: https://caucasusbarometer.org/en/cb-ge/TRUCRTS/

Note: The figure displays the percentage of respondents who reported distrust towards Courts.

Unless there is a wholesale collapse of the Georgian public health system due to the pandemic, the opposition diametrically changes its electoral strategy, or the emergence of a sweeping last-minute scandal involving the ruling party (similar to the 2012 prison videos), GD appears to be staying in power for a third term. This scenario does not look promising for Georgia’s democratization process as GD rule in recent years has been characterized by “democratic backsliding” and informal governance with no sign that this tendency would be reversed should GD win. Perhaps most importantly, having a party in power for more than two terms constitutes an acute challenge for democratization in the Georgian reality. Single-party dominance in aspiring democracies often leads to declining general standards of democracy including further deterioration of the system of checks and balances, transparency and accountability of ruling regimes.

[1] Givi Silagadze is a junior policy analyst at Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP)